STEP 1: THE FIRST STEP

MAURICE MOLYNEAUX

Where has the time gone? According to the cover, this is the 35th issue of ST-LOG. That's just one issue shy of three years! But wait. The first ST-LOG magazine hit the stands at the end of 1986. "That's not three years!" you say. That's because the first issue was actually the tenth. ST-LOG appeared as an "insert" in ANALOG Computing for nine issues prior to the big split. So, technically, this is the 26th ST-LOG magazine.

Twenty-six "real" issues, and Step 1 has appeared in all but two of them (issues 10 and 22). In a way, Step 1 has been a part of this magazine since the beginning. From my estimation, the only regular feature to appear in ST-LOG more often than this column is Ian's Quest, coming in at twenty-five issues. But as far as total wordage goes, I can proudly say I've written more than any other ST-LOG regular. Step 1 has usually been the largest regular feature, and an approximate count puts the total (including this issue's column) at over 96,000 words, more words than appear in an average 200-page paperback novel.

But all good things must come to an end, and with this issue Step 1 takes its final bow.

Why? There are several good reasons. First, in the course of twenty-three articles, I've covered everything from basic hardware and software to telecommunications and GDOS, and on the way taken a look at graphics, animation, utility programs and so forth. There's little "beginner" material left to cover.

The second reason is fatigue. Cranking out 4,000 words per month of beginner/novice-level material is no easy trick, particularly when topics appropriate for your audience become harder and harder to find.

And no, this is not some overdramatic way of launching a Step 2 column (the one that my friends joked I would eventually be forced to write). There won't be one.

This isn't to say I'm bowing out of the ANALOG/ST-LOG family either. The only way you're getting rid of me any time soon is if I'm dragged off kicking and screaming. I'll continue writing about Atari computers, but no longer in the monthly capacity of this column.

But before I go on to the subject of this final Step 1, I'd like to say "you're welcome" to all the readers who've enjoyed and/or been helped by these articles. The most gratifying part of writing Step 1 has been the response I've gotten from you readers. I've gotten quite a few "thank you" notes over the past two and a half years. Believe me, it's a great feeling to know you've been able to help so many people in even a small way.

So, I'd like to return the favor by saying "Thanks" to you readers. It's been fun.

The ST world today

I decided to dig up the first few Step 1s just to see how much different things were then from now. In a way, I'm surprised at how little things have changed. The ST's market presence in the U.S. is still weak, a lot of the available software still has serious problems. Atari still hasn't shipped the CD-ROM. The blitter chip finally appeared in the Mega STs, but plans to "retrofit" existing 520 and 1040 machines have been abandoned. No major hardware upgrades have appeared, like an ST with slots, a faster processor or improved graphics and sound. The AMY sound chip is as much a piece of vaporware as it was when the ST was first announced. Single-sided drives are still (unfortunately) with us, and people still complain about Atari's market and customer support.

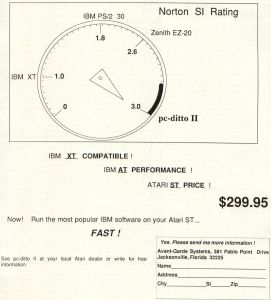

pc-ditto II

By Avant-Garde Systems

Then again, we've gotten better hard disks, laser printers and multi-megabyte STs. Third-party peripherals, such as genlocks, big-screen monitors, color-palette booster boards and boards with faster microprocessors have also appeared. The ST is the #1 MIDI computer and a top seller in Europe. All fine and good, but not quite what we'd all hoped and expected.

And the users haven't changed much either. It seems the ST attracts a lot of first-time computer buyers who are attracted by its low price and ease of use. I imagine that if I had started writing Step 1 with this issue instead of way back in late 1986, the response to it would have been about the same as it was then.

If one thing has changed, it is that it seems users—even new users—are more aware of what they want their computers to do. Desktop publishing, graphics and animation, etc., are now good reasons to purchase an ST. It proves what many of us suspected all along: The average person needs a good reason to buy a computer. Offering a low-priced machine does not ensure success. (Are you listening, Atari?) The one good thing about this is that users who buy a machine for a specific and useful task are less likely to be disappointed and badmouth it. This is because they have more realistic expectations than those who bought one because they expected the computer to "do something" for them. Which brings up the question of. . . .

A white elephant

Why did you buy a computer? Think about that for a moment. Did you purchase it because you were interested in computers, or did you have a specific task in mind? I've seen many people buy computers to "balance my checkbook." Puhlease! Spend a thousand dollars or more to do what you can do with a pocket calculator? Not so oddly, most people who purchased a computer for such a reason never use it for that task. Either it becomes an expensive video game or it collects dust in a dank closet somewhere in the bowels of their homes.

Why? Because more often than not, these people expected the computer to do something for them. The computer would make them more productive, help them manage their time, make them better writers, musicians or whatever. But in 99 percent of all cases, it does none of these things; the computer doesn't live up to the expectations it was purchased under. It becomes an expensive and essentially useless object—a high-tech white elephant.

But what went wrong? Was it that the purchaser's expectations were too high, or that the computer was simply incapable of doing the tasks expected of it? Both, and maybe neither.

The "Enabler"

As I stated last issue, a computer by itself won't do a thing for you. A present-day personal computer is essentially a complex and flexible programmable calculator—a stupid piece of hardware that processes 1s and 0s. Give it some instructions, and it does precisely what it's told. No more, no less. It can't think, it can't help you when you're in trouble. It won't teach you to be a better anything. It's just a multimillion-bit number cruncher with a fancy name.

If that's so, why do computers have such a reputation as machines that will change your life, even though the majority of buyers find their lives and working habits changed not one iota?

I think it's because there is some truth to the notion that computers can change your life, but the problem stems from the fact that the statement says one thing, yet means another. It says, "a computer can change your life," which implies that the subject, the computer, is what's making the change. The statement should read, "You can use a computer to change your life." See the difference? In the latter statement it is you who are the subject, you making the changes. The computer itself does nothing; rather, how you use the computer makes the key difference.

Let's say you bought a copy of Suzan Haden Elgin's The Gentle Art of Verbal Self-Defense. (This is not an endorsement of the book; I'm just using it as an example.) Putting that book in your bookshelf isn't going to do anything for you. Reading the words within it won't help either. However, if you use the knowledge you've gleaned from reading the book, you may find that you can hold your own in arguments much better than you have in the past.

You purchase an ST and a copy of WordPerfect. Putting that software on the shelf or using it to print recipe cards is not going to make you a better writer. Writing a story and running the spell-check on it won't do it either. To be a better writer, you have to critically and honestly evaluate your work, edit and rewrite, and never settle for what you have as "okay." You always have to look at how to make it better.

Using the computer to make you a better writer means taking advantage of its ability to make easier the task of typing the words. You don't have to retype pages to insert a missed paragraph or change a name. You don't have to watch out for the right margin or getting to the bottom of the page. You don't have to spend time worrying about typographical mistakes. You can fix and change these at any time. The distracting aspects of the writing process have been minimized so you can concentrate on the actual act of writing. You can work more quickly and easily. The computer and software have taken away some of the burdens, allowing you to concentrate on the task at hand and also permitting you to freely experiment. You can easily try adding a phrase, deleting a line or moving a paragraph, and if you don't like it, you can have the text back in its original form as quickly as you made the changes.

Try that with a typewriter.

So a word processor won't make you a writer, a paint program won't make you an artist and a desktop-publishing utility won't make you a typesetter. But if you learn to use these tools, you can educate yourself in the principles of these fields and you may be able to use that knowledge to your benefit. How many of you would be willing to type a 130,000-word novel (about 600 double-spaced pages) five times over? How about typing it once and then editing and retyping only the parts you feel need changing? More likely the latter than the former. You can do the latter with a computer, but not with a typewriter. Proper application of a computer can lessen the actual time and grunt-work needed to do the job, thus making it more likely you will succeed in completing the project.

The key thing here is that you must initially have the drive and determination to do the work at all.

Could you afford a real typesetting system or a graphics workstation? Would you try to get a job at a magazine or a video-graphics studio just to see if you liked or could do the work? Would you be willing to start at the bottom and maybe someday get the chance to be in a position to do what you really want to do? Probably not. However, you could buy a desktop-publishing program or animation program for your ST and get some experience with the basic principles of the field, and then decide if you want to pursue it any further. You can also do respectable work on an ST for a lot less money than you'd pay for typesetting equipment or a graphics workstation.

This is how personal computers can be used to improve or change our lives. Like anything else worthwhile, it requires effort on our part. The main difference between doing it with the computer or by another means is that the computer may allow us to do it more simply, with less effort and/or less expensively than otherwise, and it allows us to experiment in our own homes.

Paul Dana (author of the Cyber Star accessory and an upcoming CAD-3D-related product) one day told me that he hated the word "computer" because it doesn't describe what a user does with it. Sure, the computer computes, but when I sit down to animate Megabit Mouse, I don't feel I'm "computing" any more than I'd feel I was "penning" when I'm sketching with a felt-tip pen. Paul said he likes to think of a personal computer as an "enabler" because it enables you to do various things. I agree with him. After all, we don't call a dedicated word processor a "binary data entry/editing machine." A word processor doesn't deal in words; like a computer (which it is), it deals with binary data. It's as much a computer as your ST. But, unlike the programmable ST, it is a computer dedicated to a single task.

Testimonials

A personal computer can be a marvelous thing indeed, if you can figure out not only how to use it, but how to use it to your benefit. Since I've been part of the ST community, I've met, written or spoken to literally hundreds of fellow ST enthusiasts, and I've seen some pretty amazing things.

And, honestly, there's something unique about people who are serious about using their computers. They seem of a different breed than the rest of the population. Computers seem to draw creative and expressive people like a magnet attracts iron filings. I've met writers, editors, marketing people, programmers, professional musicians, artists and educators, a community united under the common umbrella of their interest in computers (and the ST in particular). Rarely have I seen other fields of interest capable of so passionately uniting such diverse personalities.

Working within the confines of this community, a capable and driven person can make some incredible strides. For example, take my buddy, Andy Eddy... please! (Just kidding.) I first started "talking" to Andy on the DELPHI telecommunication system back in early 1987. Andy had been writing reviews for ANALOG Computing, ST-LOG (a brand-new magazine then) and also for Atari Explorer. He was working for a cable TV company in Connecticut. Within a year of that meeting, he and I had created a pair of Cyber Studio design disks, and only a year and a half after that, he'd stepped up to and beyond a monthly column for ST-LOG (Database DELPHI) to being associate editor of ST-LOG and executive editor of VideoGames & Computer Entertainment. Quite a leap, professionally speaking.

As for myself, back in late 1984 I was working for a large mining company, running a computer in a regional field exploration office. That Christmas I bought myself an 800XL. By May I'd purchased a 130XE (then brand new) to replace the 800XL. And then came that fateful day at the tail-end of summer when I plopped down $937.50 for a just-released 520ST, an SF354 disk drive and SC1224 RGB monitor. About six months after I purchased the ST, I sold my first article to ANALOG ("Pixel Perfect," issue 47). Two months later, I sold another article ("Customizing the GEM Desktop," which later became the fourth Step 1 article). By mid ’87 I had started writing the first Step 1 articles. The turning point for me was being able to capitalize on those small successes.

As I was suddenly "press", I was able to make contact with people in the software industry that I'd have had little luck trying to contact had I not been a published writer. One of these contacts, Stephen Friedman, provided me with the then-Beta Art & Film Director programs, with which I made the Star Trek demo. This led to the Art & Film video I made for Epyx. Creating Megabit Mouse for that video got me a lot of work. I managed to capitalize on that, and I've since done game graphics for Omnitrend Software, manual designs for CodeHead Software, covers for ST-LOG and VG&CE, consulted for Epyx....

Did I mention I quit my job with the mining company in early 1987 and have been freelancing ever since?

The point here is not to show off or toot my own horn for those of my friends who are in the industry, but to show how people can capitalize on their interest in computers and use that to lever themselves into new experiences, or even new careers.

If you're wondering what the point of this exercise is, this is it: If you use your ST just to play games, it's a game machine. If you only use it for letter writing, it's a word processor. If you only balance your checkbook, it's an expensive pocket calculator on steroids. It will do nothing more for you than you make it do. The computer is what you, and you alone make of it.

And that is the final lesson. The first step in doing anything with your computer is to use it.

There is no promise that even the greatest effort in using a computer will ensure your reaching your ultimate goal. There are no guarantees. Then again, through really using your ST you may learn of paths to destinations you'd never before seen or considered. The possibilities are there—if you have the determination to search for and follow them. That's quite a package of possibilities, considering how little you have to pay for it. In my humble opinion, it's more than worth every last penny.

Class dismissed.

The staff of ST-LOG would like to thank Maurice for every syllable of those 96,000 words he's written since the beginning of Step 1. He is, without a doubt, the hardest-working author we've ever had the pleasure to work with, and although we wish we could change his mind about not continuing this column, we respect his wanting to get on with other projects. Hopefully, many of those projects will appear in ST-LOG.

Maurice Molyneaux is a longtime user of Atari computers whose interests cover writing, graphics and animation. He enjoys good science fiction, loathes "rap music" (an oxymoron if ever there was one) and loves watching old Warner Bros. cartoons. Ideally, he would like to pursue a career creating animated films.