IAN'S QUEST

by Ian Chadwick

Fantasy. Magic. Elves. Dragons. Wizards. Dungeons. It's very popular stuff, both in book and game form, maybe more so right now than traditional science fiction. Chadwick's theory is that, if you can't write science fiction, you write fantasy. If you can't write fantasy, you write horror. And if you can't write horror, you write campaign speeches. (And after that maybe computer-magazine columns?)

There's a big tendency in fantasy literature to use magic as a deus ex machina: You write your characters into an impossible corner and zap ’em out of it with some sort of spell. Shabby, but effective if your audience isn't any too discriminating. Yes, yes, there are plenty of good writers who don't use such simple, expediencies—Ursula Leguin, Barbara Hambly and so on. But it's an easy technique and one too often used. Even major authors like Robert Silverberg (Majipoor Chronicles) are guilty of it.

A lot of writers—of books and games—never think out a coherent philosophy of magic first. It's sort of like faster-than-light travel in shoddy science fiction novels—assumed, used, never explained. Some effort at control is attempted by making magic work like a rechargeable battery, but I've never understood the arbitrary distinctions between who can and can't use magic. Why can't my fighters cast spells? Or inversely, my wizards use edged weapons?

What is magic anyway? An extension of human abilities? Increased hearing, strength, endurance, healing, that sort of thing? Or is it paranormal—fireballs, sleep spells, teleportation and so on? In fact, it doesn't matter, as long as the concept is coherent and consistent through-out and, to be dramatically interesting, has limitations and weaknesses that don't allow it to supercede all other elements.

Nor is much concern ever given to the environment in which the action takes place. How many times have you played a fantasy game where the landscape was dotted with extensive dungeon or cave complexes, full of monsters and treasures? Didn't anyone ever wonder, since the time frame is almost always pseudo-medieval, how (and why) someone engineered a ten-level-deep dungeon, a sort of inverted skyscraper, then abandoned it? I've looked at a lot of real castle plans, and I've seldom seen anything two levels deep into the earth, let alone ten!

So here's a place with no light, no air ventilation or drainage. It's obviously not designed for human habitation, since it has no heating, bedrooms, dining rooms or washrooms. But there are often shackled skeletons in cells and torture chambers in abundance. Some of these dungeons could hold enough prisoners to fill an entire town and have more torture equipment than the Spanish Inquisition! But inside this inhospitable, dank, cold basement are hundreds of bizarre creatures—products of an alien, post-nuclear ecology? What do they eat? Why don't they leave spoor? And for some odd reason, they've aligned themselves on the levels according to their strengths; the weaker they are, the closer to the surface they'll be found.

Monsters. Ghosts. Demons. Rock squids. All merrily cohabiting with each other in peace, but bent on the absolute destruction of any human(oid) who might enter. And extremely protective of the gold and jewels they themselves can neither spend nor use.

Where does this bizarre impression of fantasy worlds and magic come from? Well, the mixed species, adventure party going on a quest owes a lot to Tolkien who popularized the idea in his famous Lord of the Rings trilogy. The quest idea itself is as old as the Babylonian Gilgamesh legend (about 6,000 years) and has come to us in many forms, one of the most popular in this culture being the Holy Grail quest. Tolkien also helped define the image of the wizard for many of us.

A lot of the rest is owed to the popularity of TSR's role-playing Dungeons and Dragons (tm) game. I first played D&D about 12 to 13 years ago when it was a small trilogy of poorly written books by Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax. Gygax somehow ended up as the only name on the credits and went on to turn TSR into a major money-maker, based on the sales of the D&D products. However, for all D&D's fullness in spells, character classes, monsters and so on, it is extremely weak in applied logic. There is little in the way of environment or ecology. It was assumed that players, in creating their own stories, would fill in the blanks. Well, a lot of people, with three-minute TV-spawned attention spans, don't seem to be able to get past the one-track dungeon-quest scenario.

What's the point in entering these places when sanity suggests we leave them alone? Simply to bash a lot of monster brains into porridge and gather up the treasures that, incongruously, seem to be lying about in random heaps everywhere? Sometimes there's a "quest" involved, but it's often a thinly disguised excuse to get you to go to the bottom level of the dungeon. The game often ends when you get the object of the quest back up to the light (or the surface). Is this perhaps a metaphor of heaven and hell?

The final absurdity are the characters themselves, the individuals the player controls and associates her/himself with. Aside from the absurd caste system (warrior, priest, ninja and so on), characters have the annoying ability to develop skills and abilities in an extremely short time. Some character called a warrior starts as weak as a kitten, barely able to lift his sword much less swing it, then practices a few minutes, gets in a tussle with a snooper-slink and comes out looking like Conan. A few more encounters and the guy's bashing everything in sight without even breaking into a sweat! An hour ago, the guy couldn't even tie his own shoelaces!

Sound a bit strained? Or even silly?

But so many fantasy games (and books) are based on this same sort of thing. Even FTL's Dungeon Master. Now it may be suicidal to criticize this very popular game, but as good, exciting and challenging as it may be, I still find it hard to become completely absorbed in playing when I find myself several levels deep into the earth, wondering who built such a thing and why.

Okay, having expressed my worries over the raison d'etre of fantasy, let me now put the other foot in my mouth and say that despite such qualms, I generally like the games. Even if I can't as readily suspend my belief in them.

For one, it's easier to suspend belief in a fantasy situation than in an arcade or strategy game, mostly because of the close association with individual characters. The violence is also less onerous. It's hard to get emotional when slugging it out with a blue worm. But when it comes to shooting a German officer in the back (in Eagle's Lair), I hesitate. I don't get much enjoyment of the slaughter present in most games.

There's also the satisfaction of solving the puzzles, mapping the mazes and, eventually, completing the quest. Unfortunately, my interest often runs out before the game is completed—most fantasy games, like adventures, take a long time to complete. So let's look at a few of the available games.

Epyx's Rogue (26 levels!) and the Temple of Apshai Trilogy (four levels in each game, some above ground) are lightweights. Rogue has a tongue-in-cheek approach to the "same old story," and amusing graphics which help relieve the blandness of the story. Apshai, a few generations better than its original TRS-80 incarnation, demands a little too much attention to the manual while playing: pause, read, play, pause and so on. Neither one is terribly memorable.

Dungeon Master (DM) attempts—aside from the rather flimsy premise and setting—to grapple with the question of magic and arrive at a viable solution. The business with syllables and mana (ever wonder where that concept began?) makes at least internal sense to the game. The authors also tried to create some non-linear events in the game to get out of the simplistic "search and destroy" treadmill in so many fantasy games. These include the puzzles that require thought and intuition to be solved.

DM's success also lies in the attention to detail and the craftsmanship they applied to the adventure. The graphics are good, the user interface quite easy—given the complex theme and the number of objects that must be manipulated—the sound good and the display clear despite the amount of information that needs to be seen. Few games have generated as much affection as DM, even to the point of third-party products (hint books and maps). It's hard not to like DM.

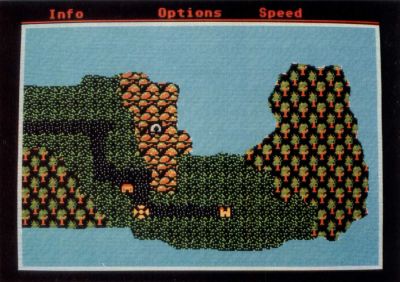

SSI may be the master of fantasy games, at least in its level of output. It has several games based on the "wander the wilderness" theme, including the Phantasie trilogy, Questron I and II and Rings of Zilfin. These are usually multitiered games in which you have to wrestle not only with the usual dungeon-type adventure, but have to solve a quest, build a party of co-adventurers, trade (buy/sell) goods in towns, explore, collect objects and so on. The "total environment" approach offers a wide variety of possibilities over the solo dungeon-type game. The "dungeons" (caves, castles, etc.) are not as deep or extensive as that in DM, but this nod to reality is offset by a large and complex wilderness in which many events occur, particularly random attacks by monsters.

Of the lot, I like the graphics and user interface in Questron (a lot like Rogue), but prefer the environment (and the more detailed game theory, if you will) in Phantasie. Both require considerable dedication and effort, but the aficionado is amply rewarded by the richness of the gaming environment. I don't much care for Rings of Zilfin's clumsy user interface, and the graphics are rather primitive. I don't think it's in the same class with the other two.

SSI has recently released a game in conjunction with TSR, based on a D&D adventure. I haven't seen it, but expect a review copy soon.

Perhaps the most interesting fantasy game is Datasoft's Alternate Reality—The City (AR). One of its main ideas is that the game changes according to how you interact with it. There is no predefined quest per se, except survival. And that's hard enough. The quest will be revealed in later "chapters" as they are released (The Dungeon, The Wilderness and others I'm told). AR mixes genres: it's also an adventure. It presents a lot of real-life situations (the need for food, shelter, etc.) with character encounters (the type depending on how you handled previous encounters) and an exercise in mapping.

While it offers good graphics, good ideas and amusing story line, AR's downfall may be in the lack of a specific goal. While many of us don't mind the wandering and exploring, after a while it gets a bit boring. After a few hours of traipsing about, building up my character, it feels like I'm "all dressed up with nowhere to go"

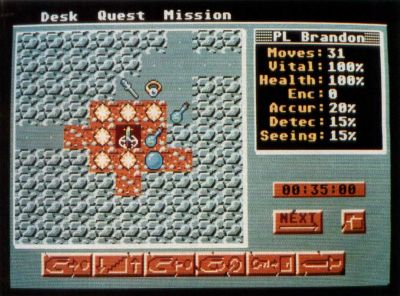

Paladin, from Omnitrend, is less of a traditional fantasy than it is a military exercise. It has all of the external trappings—caste characters, magic, monsters—but it is a spin-off from their popular game Breach and is designed as a tactical-level war game with fire spells replacing grenades and that sort of thing. However, with that in mind, Paladin is, nonetheless, quite enjoyable. It is easy to learn and play and appeals to the player who enjoys the slam and bash of combat. The quests are minimal, the puzzles simple and the action plentiful. There is even a scenario-design kit—it's the only game mentioned here which offers one. The real weakness in Paladin is the lack of diagonal movement and facing.

Personally, I'd like to see a lot of the elements of these games combined—the game interaction of AR, the graphics and interface of DM, with the scope of Phantasie. If I had my druthers, I'd like a modern fantasy. Get away from the medieval line. Make it magic in New York, say, with adventures in the subway and the sewers. An alternate universe that intrudes on ours is always good for a story. Zap the gangs with a sleep spell, battle sewer alligators and tenement rats, explore the Museum of Modern Art and Central Park. Wizardry versus bullets, swords against switchblades, cars jousting with dragons. Throw in the usual lot of monsters and evil magicians, a few quest objects. It would be a bestseller!