THE WORLD INSIDE THE COMPUTER

Winnie The Pooh's Alphabet Adventures

Fred Dignazio, Associate Editor

One afternoon while Eric was riding his Big Wheel bike on the sidewalk in front of his house, a brown UPS truck pulled up, and a man hopped out and put some giant boxes on Eric's front porch. Eric went and got his dad. His dad told him that inside the boxes was a new NEC Trek home computer that had been sent, on loan, from the NEC Home Electronics Company in Elk Grove Village, Illinois.

They set the computer up in Eric's bedroom. He liked the computer. It was neat to look at, with its ivory case, and its gray and orange keys. It was easy to use, too. He used its Micro Painter program to make pictures and its Electric Pencil program to do lots of gobbledygook processing.

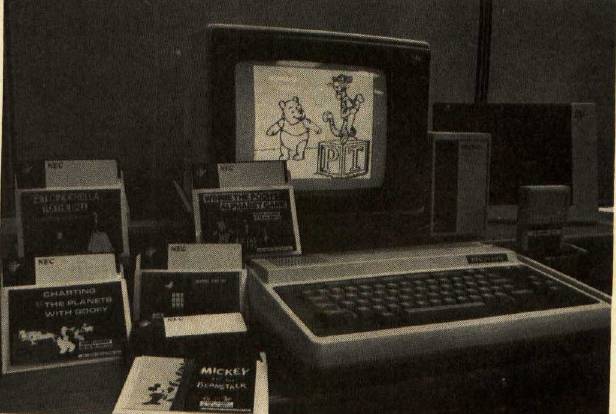

The NEC Trek was special, too, because it had games with all of Eric's favorite Walt Disney characters. He wanted to play the games and see Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Cinderella, the 101 Dalmations, and Winnie the Pooh. But, so far, he still hadn't played any of the games.

His dad had lots of excuses to explain why the games weren't ready. He mumbled something about RAMs and ROMs and an extended BASIC cartridge that hadn't arrived.

Eric already had a game disk with the word WINNIE written in big letters in blue ink. The disk had a game called Winnie the Pooh's Alphabet Adventures. But his dad told him that they still didn't have a disk drive to put the disk into.

He really wanted to see the Winnie the Pooh program, so he put pressure on his dad to get his act together and find the equipment they needed to make the program work.

Pretty soon, more big brown boxes started arriving in the mail. Eric loved opening boxes. He had never run into a box he couldn't open. When he was only six months old, his parents put a box around him, with holes for his head, legs, and arms. On the side of the box his dad drew, in big letters, the words PAPER SHREDDER. And he drew lots of pretend dials and switches. It was Eric's first Halloween costume. He went to three Halloween parties, crawled around on the floor, and shredded any paper that he found in his path.

Fred D'lgnazio is a computer enthusiast and author of several books on computers for young people. His books include Katie and the Computer (Creative Computing), Chip Mitchell: The Case of the Stolen Computer Brains (Dutton/Lodestar), The Star Wars Question and Answer Book About Computers (Random House), and How To Get Intimate With Your Computer (A 10-Step Plan To Conquer Computer Anxiety) (McGmw-Hill).

As the father of two young children, Fred has become concerned with introducing the computer to children as a wonderful tool rather than as a forbidding electronic device. His column appears monthly in COMPUTE!.

But Eric wasn't a baby any longer. He was four years old, and he could shred boxes the way he used to shred paper. When the computer boxes arrived, he opened all of them with his bare hands. Inside the boxes were the computer parts his dad had told him about. He helped his dad attach all the parts to the main computer that was sitting on a little table in Eric's bedroom.

Run, Winnie, Run!

Finally a box came with the last part. Eric huffed and puffed and "Hulked" open the box. Then he and his dad raced to his bedroom to put the missing part into the computer.

His dad turned on the power. The computer worked! Eric hopped around the room. He almost fell on the computer, he was so excited.

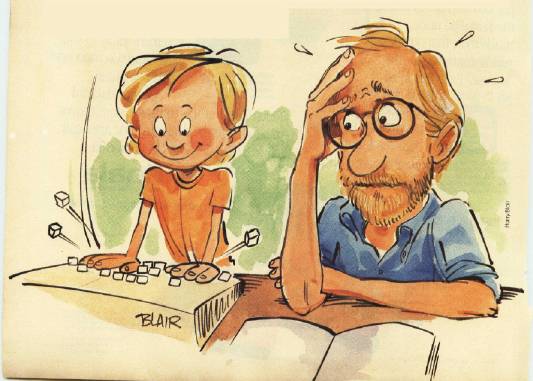

His dad let him put the Winnie the Pooh disk into the disk drive. He let Eric do everything on the computer all by himself. While he was working on the computer, sometimes he saw his dad put his hands over his eyes. Sometimes he saw him grit his teeth and look like he was going to cry. Sometimes he even heard him growl. But he always let Eric do everything. Because of this, Eric was getting pretty good at computers, even though he was only four years old.

His dad read from the NEC manual for the Alphabet Soup package. Eventually there would be two programs in the package: the Winnie the Pooh alphabet game and another game called Mickey's Lucky Stars. Mickey's Lucky Stars would teach Eric how to match small letters in the alphabet with big letters; and help him learn which letters come before other letters and which ones come after.

Eric's dad read the commands from the manual. He repeated the letters, one by one, and Eric typed them into the computer. When he was done, the command RUN "winnie." was on the screen. He pressed the RETURN button to send the command to the computer.

Out of the computer's speaker came the song "Winnie the Pooh," and the Pooh bear himself appeared on the screen. Beside him was a big, yellow, blinking question mark.

Just then the telephone rang, and Eric's dad took off. "I'll be right back!" he called.

"Sure," Eric thought. "In about a million years."

Eric didn't feel like waiting a million years. Besides, he knew what to do next, even without a manual. When he saw a question mark on the screen, that meant the computer wanted him to type something in. "But what should I type?" he wondered. He picked his favorite word: ERIC.

He typed an E, then began searching for the R. But before he got there, the disk drive light came on, the drive began clacking like his Big Wheel bike, and Winnie the Pooh vanished from the screen.

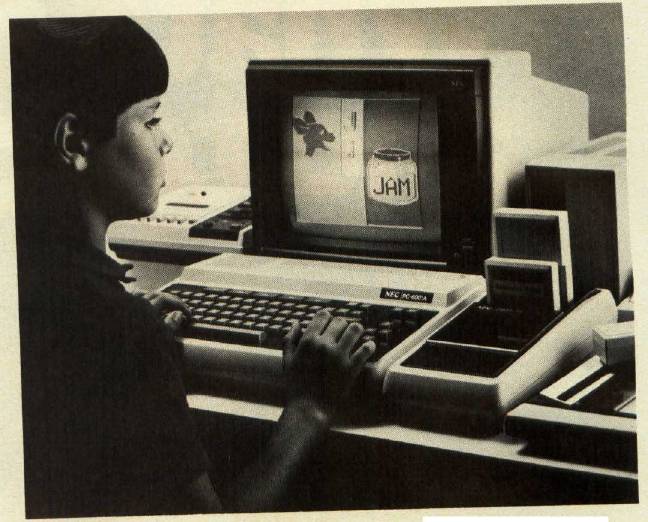

A moment later, a new screeYi appeared. It was divided into several rectangles, each a different color. The Winnie the Pooh character, Tigger, appeared in the upper left-hand corner of the screen. In the upper center portion of the screen, two E's appeared — one uppercase and one lowercase. On the right-hand side of the screen was an elephant. In the lower left-hand corner of the screen was a yellow box. The box was empty.

All these things appeared on the screen, but Eric didn't notice. He was still busy typing his name. He typed an I and a C, then he looked up.

His dad sailed back into the room. He looked at the screen. "Hey, that's great, Eric," he said. "How'd you do it?"

"By typing my name," Eric answered, not sure whether to be proud or puzzled. "It made an E, but it didn't make an R. Or an I. Or a C."

I Know What To Do!

"I wonder what we do, now," his dad said, peering closely at the screen. The NEC company had sent Eric and his dad about ten pounds of computer manuals to assist them on the computer. But the two of them rarely used manuals, especially when they were just getting started. The fun part of running new programs was to see if they could make them work without reading the instructions.

Eric's dad was naturally cautious around computers. He tried to figure out which button might make the program do something.

Eric had a better approach. When he didn't know what to do next, he pressed all the buttons.

His strategy worked. After only a few seconds and a couple of dozen buttons, he found one that did something. He pressed the DEL (Delete) key, and the empty yellow rectangle in the lower left-hand corner of the screen turned blue. He pressed the button again and it turned red. Then it turned green. Each time he pressed the button, it turned a new color.

When Eric pressed the E key, the computer played a little more of the Winnie the Pooh song then went back to the picture of Pooh and the big question mark.

"Hey!" Eric said. "E makes a picture. Then E makes the picture go away."

He pressed some more keys. He eventually made it up to the orange function keys on the top of the keyboard. When he pushed the F4 key, Winnie the Pooh, Tigger, and Rabbit appeared on the screen and, with musical accompaniment, waved goodbye.

"Oh, terrific!" said Eric's dad, more than a little distracted and disturbed by Eric's shotgun approach to using the computer. "Now you've terminated the program, and we've only gotten to see one letter."

Eric was momentarily stymied. But at the moment he felt like he could do anything — the way he felt when he was rustling up a jellybean, Cheerio, and dry-noodle stew in the kitchen, or tying his shoes, or stirring up Mowie's breakfast of gooky cat food and kibbles. He surveyed the keyboard. Then he was ready. "I know what to do," he said confidently, and began pressing all the keys at the same time.

He got to the F5 key and pressed it. Winnie and his friends disappeared. The title frame came back on. He had restarted the game. He looked up at his dad. "See?" he said.

All It Takes Is Teamwork

Eric and his dad worked well as a team. With their combined brainpower and Eric's penchant for button pushing, they soon figured out how to use the rest of the program.

For example, when Eric pressed the Fl button, the NEC thermal printer started making noises like a tire spinning on ice, and paper started creeping out with a copy of the picture on the computer display screen.

Eric loved this part. Printing pictures was so easy! Very quickly, his bedroom floor filled up with 4-inch by 4-inch scraps of paper featuring all the Pooh characters and creatures whose names began with every letter from A to Z.

Solving The Mystery Of The Blank Box

The blank box in the lower left-hand portion of the screen was the greatest challenge. Even when Eric printed out the display screen, the box was empty. Why was it empty? Either the program was broken and the box was supposed to have something in it, or Eric and his dad were supposed to put something in the box themselves.

They tried using the joystick. That didn't work.

They pressed all the keys on the keyboard again. No luck there, either.

They were about ready to give up and peek at the Winnie the Pooh program's instructions. Then they figured it out. They could fill up the box by drawing things on the NEC Trek touch panel, a flat drawing tablet that reproduced a copy of a picture on the computer's display screen.

The touch panel freed Eric from the computer keyboard. And that's when the real fun started!

His dad went into his study and cut up lots of pieces of paper to fit on the touch panel. Two flexible magnetic strips held each piece of paper on the panel so it wouldn't move about.

Eric climbed on the metal truck and, on top of his dresser, found the black felt-tip marker that NEC had supplied with the touch panel.

He began drawing on the panel. He drew circles, triangles, straight lines, and random squiggles. Then, satisfied with his artwork, he pressed the Fl button and printed his picture — complete with a letter of the alphabet (in upper-and lowercase), a picture of an animal whose name began with that letter, and a character from Winnie the Pooh.

Eric then took the pictures he had just drawn and put them onto the touch panel. He created new pictures by tracing the animals and letters on the old pictures. He created drawings that looked reasonably like Winnie the Pooh, skeleton hands, elephants, alligators, and birthday cakes.

For Eric this was a thrill — such a thrill that he drew pictures on the touch pad, picture screen, and thermal paper for another two hours. And the next morning, when he woke up, it was the first thing he wanted to do, even before his all-important bowl of Cheerios.

Drowned In Alphabet Pictures

The night before, after the first hour, little scraps of paper were all over Eric's bedroom. Eric wanted to create a picture for each of his pets (his robot Denby, his puppy, and his kitty), for each member of his family and all his friends. Each picture had the first letter in the name of the person or creature it was going to.

Paper scraps flooded the bedroom, and his dad grew alarmed. He had visions of being drowned by Pooh pictures. He suggested that Eric try to group the papers into piles.

To his dad's relief, Eric came up with the idea to make "books" out of several of the pictures. The letters could be grouped together to make alphabet books, or to form the complete names of his mother, father, sister, grandparents, cousins, and his pets, creatures, and friends. He and his dad got busy and turned Eric's bedroom into a miniature printing company. They stapled the pictures together into books, and they taped lots of pictures together on pieces of notebook paper to spell words and names, and make signs that spelled things like MOWIE, WINNIE, PIGLET, EEYORE, ERIC, CATIE, and BACK OFF! The flow of loose paper scraps slowed somewhat, but not enough. Out of desperation, Eric's dad peeked at the instructions to the Winnie the Pooh program and discovered lots of additional activities using the alphabet-pictures that Eric was churning out of the computer.

Buying A Ticket To The Magic Kingdom

Walt Disney software runs on the NEC Trek computer (also known as the PC-6001A). Here are the prices of the components of a minimal NEC Trek system that will take full advantage of the software's features:

| NEC Trek Computer (PC-6001A) | $349.95 | |

| DiskUnit(PC-6031A) | 549.95 | |

| Data Recorder (PC-6082A) | 99.95 | |

| Expansion Unit (PC-6011A) | 99.95 | |

| Extended BASIC Cartridge | 49.95 | |

| 32K ROM/32K RAM Cartridge | 49.95 | |

| Touch Panel (PC-6051) | 149.95 | |

| Thermal Printer (PC-6021A) | 249.95 |

Of course, you will also need a monitor or TV set to run the Walt Disney software.

The NEC Trek is an excellent home computer system. It is attractive, its full-sized keyboard has a nice touch, and the display on computer screen is beautiful: Large white characters are displayed on a rich green background, and helpful function keys are displayed, as a reminder, at the bottom of the screen. The system's components are equally attractive and are reliable, easy to attach, and easy to use.

But do you need all the components above to run the Walt Disney software?

You need most of the components, but not all. The Walt Disney software will be sold on cassette and disk, so you need to buy a data recorder ($99.95) or a disk unit ($549.95), but not both. The data recorder is the way to go if you have a tight budget, but I don't recommend it. The Disney software takes up a lot of space in the computer's memory. Loading the programs from cassette will be tedious and time-consuming — not the way to get started on a fun learning activity with your child.

In addition, you do not need the touch panel ($149.95) or the thermal printer ($249.95) to make the software run. However, if you elect to go this low-budget route, I think that you'd be better off (in the case of "Winnie the Pooh's Alphabet Adventures") with an inexpensive alphabet book for your child. The touch panel and the thermal printer are the keys to making the software interactive and a joyous experience for a young child (see my accompanying review with my four-year-old son Eric). Young children can use the touch panel and the thermal printer and create their own alphabet books.

Winnie the Pooh's Alphabet Adventures will be part of a two-program package entitled Alphabet Soup. The other program will be Mickey's Lucky Stars and will teach letter sequences. Alphabet Soup is already available. It is just the first of five Walt Disney software packages. The packages teach the letters in the alphabet, reading, writing, spelling, and arithmetic. They will also help develop a child's problem-solving, logic, and fine motor abilities. Each package will cost $34.95 (disk or cassette).

I will review the forthcoming Disney packages in future issues of COMPUTE!. The reviews will appear about the time that each package is released. Here are the titles of all the packages and programs:

Alphabet Soup (Ages 3-7)

Winnie the Pooh's Alphabet Adventures

Mickey's Lucky Stars

Goblins & Galaxies (Ages 9-14)

Minnie and the Haunted Mansion

Goofy in Space

Mathemagical Maze Craze (Ages 7-12)

Cinderella's 3-D Maze

Mickey's Mathemagical Mops

Race To The Arcade (Ages 7 - 14)

Donald's Word Arcade

Dalmation Multiplication

Countdown Carnival (Ages 7- 10)

Mickey and the Beanstalk

Cinderella's Beads

If you want to learn more about the NEC Trek (PC-6001 A) computer and the Walt Disney software, write or call:

The Personal Computer Division

NEC Home Electronics USA

1401 Estes Avenue

Oak Grove Village, IL 60007

3121228-5900

They began to use the pictures as alphabet flash cards and played lots of games, including Concentration (guess the missing letter), Scrambled Letters (trying to reorganize letters to make up a word), Letter Match (matching up lowercase and uppercase letters), Tasty Letters (matching up flash cards with alphabet cereal letters), Alphabet Clothes Line (taping the letter pictures to a string hanging in the room), Mystery Letters (letting Eric run his fingers along the clothes line, and trying to guess which letter he is pointing to).

The Winnie the Pooh user's guide even had a short BASIC program to type in to create a new game. Eric and his dad typed in the game. It was a Mystery Letter game. It typed a sequence of letters on the computer's display screen, but one letter was missing. Eric had to guess the missing letter. If he got the letter right, his dad let him print the letter out on the computer printer.

Typing With His Toes

The more Eric used the Winnie the Pooh program, the more relaxed and creative he became. In the beginning, he sat stiffly in front of the computer keyboard and picture screen, held the touch panel in his lap, and drew on sheets of paper. But by the end of his first session things had changed drastically. His dad lay on his side, sprawling behind Eric, watching him draw his pictures. Eric decided he wanted to get more comfortable, too, so he climbed up on his dad, using him as a reclining lawn chair. He stopped using the paper and marker to make pictures and, instead, began drawing pictures with his finger on the white, glossy plastic surface of the touch panel. It was like electronic finger painting, and he loved it!

When Eric climbed on his dad the first time, he accidentally kicked the Expansion Panel on the side of the computer. Loaded in the Expansion Panel were a RAM cartridge and the Extended BASIC cartridge needed to run the program. When the Expansion Panel became dislodged, the screen went blank and the program disappeared.

Eric pushed the Expansion Panel back against the computer, but he didn't want to reboot the disk (he'd already done that before), so his dad had to do it. While the program was reloading, Eric did backward somersaults across the bedroom floor.

His dad lay back down. Eric stopped doing his somersaults and climbed onto his dad again. As he was making himself comfortable, he pulled the cord out of the touch panel. His dad saw the cord fall off, but he didn't say anything. Eric spent about a minute making a drawing with his finger before he looked up at the computer's picture screen. The little picture box was still empty.

Eric pushed all sorts of buttons on the computer before he realized that nothing was happening because the touch panel was no longer connected to the computer. This prompted his dad to deliver a little lesson on computer cables as "highways" for the computer's information to zoom back and forth from the computer to peripherals like the touch panel and the printer.

Eric and his dad also discussed the pins on the ends of the cables, so that Eric would know the proper way to plug the cables into the computer and the other equipment.

Eric got the touch panel hooked up. He climbed back up on his dad, dug his elbow into his dad's rib cage, and began drawing. But now the touch panel was upside down. This appealed to him. Everything he did on the touch panel showed up backwards and upside down on the picture screen.

He tried typing the letters in his name. He tried making numbers. He made faces, houses, and robots. Everything appeared on the screen backwards and upside down.

Eric turned the touch panel on its right side and drew pictures. Then he turned the panel on the left side. Then he turned the touch panel over and tried to draw pictures on its bottom. When he found that this didn't work, he improvised by drawing a picture with his knee.

When he was done drawing, he said, "Daddy, please press the print button."

"Phooey!" his dad said. "You're lying on me. How am I supposed to press the button?"

"Please, Daddy?"

When his dad heard that "Please, Daddy?" he couldn't resist. "I'll see what I can do," he said. He looked down at the computer. His bare, sockless foot was only a couple of inches to the left of the keyboard. He lifted his leg carefully (so as not to dislodge Eric and his touch panel) and stretched his big toe toward the Fl button on the keyboard. He missed. The computer made haunted house music to show that he had pressed the wrong key.

He tried again. This time his toe hit the right button. The printer started chugging away and printed Eric's picture.

"Wow!" Eric said, impressed by his dad's display of pedal dexterity. Unfortunately, this gave Eric ideas. It opened his eyes to new ways to interact with computers. He knew that using his fingers was OK, and his sister had once operated her computer using her tongue. But he had never considered using his toes. Until now.

The rest of the evening Eric practiced pressing all the buttons on the NEC Trek with his toes.

He did pretty well, too. And his dad let him do it. But his dad created one rule that Eric had to obey. Before he could continue using the computer, he had to submit to a thorough sponge bath of both feet.