ATARI CAFE

World's First Computerized Coffee Shop

It's the last place you'd expect to find innovative technology. Cedar Ridge, California, pop. 201, high in the former gold-mining country of the Sierra foothills, 200 miles from the smog and neon lights of San Francisco, seven miles off the main highway leading to the casinos of Reno, Nevada. Out in the middle of nowhere.

It's the last place you'd expect to find innovative technology. Cedar Ridge, California, pop. 201, high in the former gold-mining country of the Sierra foothills, 200 miles from the smog and neon lights of San Francisco, seven miles off the main highway leading to the casinos of Reno, Nevada. Out in the middle of nowhere.

Route 174 is a narrow strip of asphalt that twists past cow pastures and winter-bare branches of almond orchards in the rolling foothills of the Sierra mountains. It veers sharply to the right, taking you on a winding tour of the business district of Cedar Ridge. Like most towns in the Mother Lode, the elevation far exceeds the population.

The sign on the roof of the Roundup Coffee Shop is bound to attract passers-by. (And why not, it's the only coffee shop in town.)

Free coffee every day

Free movies every night

Free video games for the kids

But this isn't "Chuck E. Cheese's Pizza Time Theater Goes to the Woods." The entrance beckons with a poster of a menacing skull and cross-bones done in that unmistakably folksy mechanical dot-matrix style of Broderbund's Print Shop software: "Warning: During closed hours the computers call police if building entered. Armed owner on premises." The skull is surrounded by a border of computer-generated hearts. Never mind the bearded-up gas pumps outside, the wall clock shaped like a stagecoach, quaint red and white checked tablecloths and curtains. The Roundup Coffee Shop is the roadside restaurant of the future.

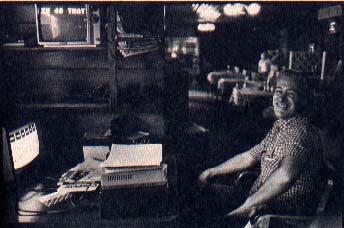

Owner Monty Carlton doesn't miss his waitress. "These are the first waitresses that I've ever had that write orders I can always read. I got tired of squinting at the hieroglyphics." He now has a crew of 13 black-and-white mechanical servants who cast a dull purple glow over the dining room of his cafe. They never get sick, they don't talk back to the customers, they'll never ask for a raise, and best of all--they can add and subtract without making mistakes. They're Atari computers.

NO TIPPING

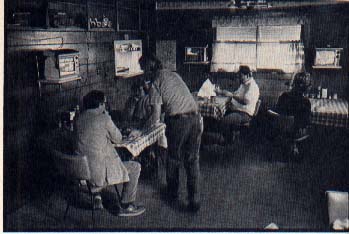

The Lunchtime rush is eerily silent, punctured by an occasional explosion, the gobbling noises of "Pac Man," or the whine of the dot-matrix printer. Outside, the sun is shining on gnarled oak trees against the bluest of blue skies. But inside it's curiously gloomy-the lights must stay dim to keep the glare off the wall-mounted television sets. The knotty pine ceiling is a spiderweb of wires, the floor a maze of power strips. Joysticks dangle from the ceiling on black wires. A banner scrolls by on the television screens: "No tipping the computer. If it has money, it may quit."

The tabletops are a still life that could be entitled: "What's wrong with this picture?" Ketchup, mustard, chrome-plated napkin dispenser. Salt and pepper shakers. . .joystick. Computerized messages flash by. "Today's Special: Homemade Chili." "Your Ad Could Appear Here for $8 a month."

It may be the last place in America where you can buy a steak dinner for $3.95. But that's not the Roundup Coffee Shop's claim to fame. Ever since Carlton replaced his waitress with a computer system, a steady stream of newspaper reporters and television cameras have made the pilgramage to what he calls "The world's first computerized coffee shop. It definitely brings in the customers-- and the free publicity," he says with a laugh.

An Atari computer enthusiast who has worked in the restaurant business for most of his life, Carlton escaped from Los Angeles and moved his family to this town a year ago. When he bought the business, the restaurant had a western theme and business was slow. Now, the crew of Ataris saves him $20,000 a year and Carlton is the only human employee. He fries up the orders in the kitchen, answers questions about the computers, brings the food to the customers and buses the tables.

BBS BURGERS

Monty's computer-printed menu features food from the heart of America. There's the "BASIC Special" (Homemade Biscuits and Gravy), the "Disk Drive" (Four Griddle Cakes and two eggs for $2.25) "Lap Top Portables" (Beverages) and "Bits and Bytes" (side orders).

The coffee shop seats 52 customers, with a joystick and an Atari computer at each of the 13 tables. Blocky, computer-generated banners advertising "Home-Made French Fries" and "Country Biscuits and Gravy" span the knotty-pine paneled walls. The accounting for the business is done with his own software on the Atari. Even the security for a restaurant full of tempting electronic equipment is taken care of by Ataris hooked up ts an alarm system.

Carlton even claims he's discovered thc first truly practical application for the Supra Micronet, a local network designed primarily for schools that allows eight computers to share the same disk drive and printer. The Roundup has two Micronets linking 13 Atari computers to two disk drives and two printers.

NO WAITING

NO WAITING

This isn't just another roadside attraction. Carlton talks about his Atari cafe with all the seriousness of a Wall Street accountant.

"The number one reason why restaurants go broke is employees," he says. The system, based on inexpensive 800XL computers and black-and-white TV sets, cost less than $400 per table. Carlton claims that it has already paid for itself.

"Look," he says as he bustles around cooking the orders and answering patrons' technical questions, "In the restaumnt business you have three main expenses--food, rent and labor. Food and rent are fixed expenses. Labor is the only place you can cut, and I've reduced my labor expenses to zero."

"The closest you can get to this is the automated teller machines at banks," Carlton says. "Once people got used to using ATMs, they got impatient with waiting for real tellers. He's taken the "wait" out of "waitress." "If a customer comes in and knows what they want, they can order from the computer and get the order to the cook immediately," he says. "How many waitresses ask you how you want the bacon cooked? It's always burned or cold. The computer can ask you questions and give you answers a waitress would never think of."

And the service is fast. It took less than three minutes for Carlton to fry up the specialty of the house--a BBS (Bulletin Board System) Burger--and deliver it to the table.

As a deterrent to non-computer orders, a message flashes onscreen, "Order from the computer and have one chance in 40 that the camputer may buy your lunch." Another banner flips by: "Today's special: Fresh Apple Pie. Chili and Beans." Press the joystick trigger and the menu appears on your tableside TV. Carlton wrote software that leads the customers through CompuServe-style displays where they make choices by pulling back on the joystick.

When an order is completed, they enter it by pressing the joystick trigger. The check is tabulated and printed out in the kitchen as the obnoxious screech of the printer drifts into the dining room. While waiting for Monty to fry up lunch, customers can pop in an Atari game cartridge and play Pac Man or Pole Position.

"THIS IS WEIRD"

"THIS IS WEIRD"

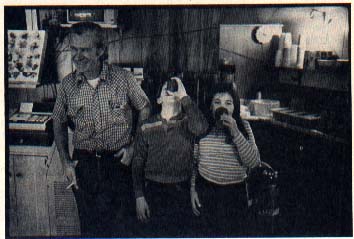

A family of four walks in off the road. They crane their necks and gawk at the black-and-white TV sets and the computer-generated banners. The kids tug Dad's shirt tails and say with wide eyes, "Daddy, this place is weird!" But as soon as the kids discover the joysticks and the free computer games, they love it. Mom struggles to figure out how to use the menu while Dad asks Monty, "Don't you end up doing more work this way?"

"No, you just have to train the neophytes," Carlton says, "If we all took to computers like the kids, this would be easy."

The Roundup isn't the first technological encroachment in the Sierra foothills. Ironically, it's on the main route leading to the town of Grass Valley where, during the glory days of videogames, Atari, Inc. had their own Camp David. At this think tank retreat started by Nolan Bushnell, several Atari innovations including the X-Y monitor and the VCS game machine were born.

SILICON FOOTHILLS

You would think that the locals of this county of sawmills and orchards would be bitter about computers-- replacing a job opportunitity. But Carlton says it's not an issue.

"The customers love the computers," he says, "People who would never even touch 'em--little old ladies 70 years old--they're delighted." Thirty regular customers already have their own private menus built into the system, recallable with a push of a joystick trigger.

The locals like the excitement the Atari Cafe has brought to town. "This ain't a town," a woman in the next booth corrects me, "It's a dot." "The Sacramento TV cameras interviewed me last week," she says. But the local residents seem to like the 1-in-40 chance of winning lunch on the house more than the TV cameras, Atari computers and free video games.

"We came in a little low on cash one day, and we ordered the cheapest thing on the menu--and, darnit, we won," she says. "The odds are better than the Califomia lottery. We call it eating to win."

The veins of gold have long since dried up. But for hometown entrepreneurs like Carlton, one frontier remains--computer technology. He plans to package Atari computers along with his software and market it as a dedicated restaurant system. "If you installed this system in a Denny's or a Bob's Big Boy, think of the money you'd save. You're talking hundreds of thousands of dollars a year," he says.