Cyber Corner

Planning Your Animation, Hollywood-Style

by Andrew Reese

START Editor

|

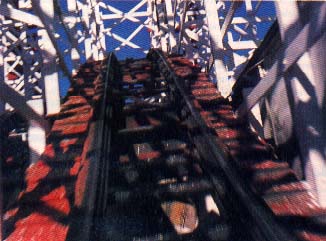

| A "point-of-view" shot puts the viewer in the place of the camera and conveys some of the feelings that the actor is presumably feeling. |

When I started writing this month's column about choosing and using different camera angles and cuts in ST animation, I realized there was a great deal of basic information that might not be available to you. So we'll put off our discussion of camera cuts in Cyber Control animation recording until later and focus on basic film, video and animation terms and concepts.

If you watch a movie, TV program or commercial, you'll see that the actors aren't the only things that move. The camera moves and its viewpoint changes, depending on what the director wants to show. The same thing can--and should--be done with your animation. But in order to be visually effective, you need to plan your animation carefully.

All commercial film, video or computer productions are planned in detail before production begins. When the cost of a day of shooting a film can easily exceed $100,000, a director spends most of his or her time planning each shot and camera angle. Well, you're the director of your own animation, but luckily, a day at your ST doesn't take a penny from your pocket. But it does take time. Let's see how to save that time by planning ahead.

Storyboarding

Every director, you included, must have an idea what the finished production should look like before beginning. It's no good just to sit down with an animation program and hope for inspiration. Experimenting with an animation program, however, is different--you have to play with it in order to understand its capabilities. Otherwise you may plan your animation around an effect your creative vision demands but that the program just can't deliver. So fool around; try out all of the program's controls and effects. You may discover something that will make your job easier or inspire you to try a new approach. But you should always begin with a clear idea.

Next a director must shape the idea in the form of a series of pictures or sketches called a storyboard. A storyboard shows a sequence of key points in a scene or production. In an animation, it shows the key frames. The actors (our animation cels, objects, sprites, clips or blocks, depending on the program) are depicted in specific positions from the viewpoint of the camera, i.e. the viewer. In an animation system that does tweening-- interpolation of an object's position or shape between key frames--the definition of these key frames is critical.

Many ST animation programs have some form of tweening. MichTron's Make It Move, Antic Software's Cyber Paint, Epyx's Film Director and Aegis Development's Animator ST all tween cels, blocks, clips or sprites between positions on the screen or between different sizes or shapes. Tweening is essential to easy two-dimensional animation. Programs like Antic Software's CAD-3D and Cyber Control, however, use three-dimensional objects and do not do tweening. Storyboarding is just as essential for CAD-3D animations, however, as it helps you define camera and object movement for later Cyber Control program development.

|

| Figure 1. A 21-frame storyboard form such as this can be used to plan an animation and minimize the animator's time at the computer. |

Storyboards can be any size that's convenient. Any good art supply store should sell a variety of different storyboard pads, complete with a TV-shaped mask and a place for notes, dialog or narration for each frame. If your local art supply doesn't carry them, contact Valiant IMC at the address and telephone number at the end of this article. They stock a number of storyboard pads of different sizes and designs. I generally use a pad with 21 frames on a single 8 1/2 by 11-inch sheet, as shown in Figure 1. Choose the size and style that fits your needs and your handwriting.

On your storyboard pad, sketch in the first position of the actors from the viewpoint you want the audience to have. You don't have to be a great artist; just make a sketch that you can understand. Next, sketch in the next key position of the actors and make a note on what has changed from the first frame, so that you can plan the movement or programming to accomplish it. Proceed key frame by key frame through the animation, ending with the final position of the actors. You now have a "script" that will help you structure your 3D program or 2D animation.

Camera Angles And Roller Coasters

Look at your storyboard. You've probably drawn your actors from different viewpoints during the animation. After all, a story told from a single fixed camera angle or viewpoint is inherently boring. The next time you watch TV, ignore the plot and action (it's easy, actually) and focus your attention on the way the cameras move and vary the size and location of what you see. Every scene has a "master shot" (also called an "establishing shot"). It's usually a wide shot that shows the actors in relation to their surroundings and gives you a point of reference to understand what's happening. Don't forget this concept in planning your animation.

But there are other camera shots that add visual interest to a scene, focus your attention where the director wants or put you in the place of one of the actors. (A camera shot can be thought of as a particular combination of camera position, angle, focus and field of view.) A good animator uses any technique that will assist him or her to tell the story.

For example, it's possible to show a complete roller coaster ride in a wide shot from the ground, but it totally lacks any visual punch. Directors, therefore, often place a camera in the roller coaster itself to give the viewer the visual impact of the ride as shown in the opening photo. This "point-of-view" shot puts the viewer in the place of the actor to share his or her experience. But how is the actor reacting to this wild ride? To show this, directors use a "reaction" shot, focusing on the wild-eyed expression of the actor as he or she plunges down the track.

These camera shots are valid, useful tools to tell a story, but using any one of them too long destroys the effectiveness of the story itself. So a director will mix them and add in a number of others as they may be needed. You, too, should vary your camera angles to tell your animation story.

Techniques

Animation is a laborious process at best. Changing camera angles or viewpoints in 2D animation requires an animator to create a new sequence for each portion of an animation shown from a different viewpoint. The actors will be seen from a different angle and so will the background. It takes a great deal of artistic ability to accomplish this in a coherent manner.

3D animation is different, however. Once you've defined an object (the hard part), it's relatively easy to change camera locations around that object or zoom in on one portion of it. This is the magic of modern computer animation--if you have a chance to see "Red's Dream," the award-winning animation by Pixar, you'll travel through a bicycle shop full of gorgeous 3D bicycles, made up of over 10,000 computer-generated polygons.

You can change camera angles in a 3D animation in two ways. First, you could record the animation several times, once from each camera angle during a separate run through the animation and then assemble it in a post-production animation package. This is the technique video and filmmakers use all the time; it puts the burden on the editor to assemble the footage correctly. Alternatively, you can record it once and cut between cameras, camera angles or locations during the one recording. If you've planned well, you should be able to accomplish your entire basic animation in one pass. This is the technique we'll focus on next column.

New Graphics Products

We're in luck, fellow graphics buffs! A number of new graphics products have hit the market or are in the pipeline as I am writing this. Epyx is releasing Art Director/Film Director in mid-summer, so it should be available by the time you read this. It's a unique addition to an ST animator's program library with capabilities found in no other product on the ST market. This package was originally set for release by Broderbund last year, but never made it. Now Epyx has picked it up, fixed some bugs and completely rewritten the documentation. It has such features as scratch-off (overlaying one picture over another and scratching off part of the front to reveal the back) and multiple sprite animation. Watch for a full review by Marcus Badgley of this package and version 2.0 of Cyber Paint in an upcoming issue of START.

The wait for high quality composite video output is over. Practical Solutions, the folks who brought you the Monitor Master and Mouse Master, is shipping Video Key. We're looking forward to putting this long-awaited wonder through its paces for you; watch this space! And if you have been pouting because the Amiga has genlock capability and the ST doesn't, pout no more: JRI is releasing a superb, reasonably-priced genlock for the ST. (Genlock lets you overlay computer graphics onto a video image.) John Richardson, the genius behind JRI, will explain the intricacies of genlock in the next START and well have a review of his product as soon as we can squeeze it into these pages!

Products Mentioned

Animator ST, $59.95. Aegis Development, 2115 Pico Blvd., Santa Monica, CA 90405, (213) 392-9972.

Cyber Studio, $89.95, Cyber Control, $69.95; Cyber Paint, $79.95. The Catalog, 544 Second St., San Francisco, CA 94107, (800) 2347001. Make It Move, $49.95. Michtron, Inc., 576 S. Telegraph, Pontiac, MI 48053, (313) 334-5700

Video Key, $119.95. Practical Solutions, 1930 E. Grant Road, Tucson, AZ 85719, (602) 884-9612.

Art Director/Film Director, $79.95. Epyx, Inc., 600 Galveston Drive Redwood City, CA 94063, (415) 366-0606.

JRI Genlock, tentative price at presstime $400. John Russel Innovations, Inc., PO. Box 5277, Pittsburgh, CA 94565.

Video Storyboard Pads, $3.95 per 100 sheet pad. Valiant IMC, 195 Bonhomme Street, Box 488, Hackensack, NJ 07602, (800) 631-0867.