|

Meet

David Crane:

Video Games

Guru

by Colin Covert

Reprinted from TWA Ambassador Magazine with permission of the author and publisher; copyright 1983 by Trans World Airlines, Inc.

This is a story about a famous person whose name you've probably never heard. He is a modern artist. His works adorn millions of homes nationwide. They command the families' attention for hours on end every week. His income is astronomical. Yet only now are he and others like him emerging as significant figures in the public consciousness.

Our subject is David Crane. He designs the most popular video games in America.

At 29, Crane is an unlikely superstar, a gangly six-foot-five coat rack of a guy with an all-American exterior and a Scientific American soul. Blond hair falls in straight bangs across his forehead, and he sports a sandy beard of recent vintage. The instruction brochure of his best-selling home video game Pitfall put his face before so many young players that people had begun requesting his signature at the supermarket. "People asked me for my autograph. I thanked them for asking," he says, bemused. That's when he grew a beard to change his appearance. Having become famous after a fashion, Crane, who is shy at parties, is striving to go incognito. Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown.

His complexion is pale by California standards; designing video games is an indoor occupation. The pitch of his voice is high, almost adolescent. His characteristic expression is a wry smile, a little grin that just puckers the corners of his cheeks. He looks uncoordinated but is by all accounts a cut-throat tennis player. And, in the estimation of many people who know him, he's a genius.

Genius means something different in Silicon Valley than it does to the south in Hollywood, where a "genius" is anyone whose latest film is making money. To computer professionals in Mountain View, Sunnyvale, or San Jose, "genius" is an accolade that implies vast technical expertise. Crane, a virtual Berlitz academy of computer languages, is also a genius in the Hollywood sense. His games are the nearest things to sure hits in the industry.

Video games--once a sizable fad, then a swelling craze--are becoming the dominant entertainment industry of the Eighties, a white-hot vortex of art, technology, showbiz, and, above all, money. Atari paid a staggering $22 million to license Steven Spielberg's character E.T. for a video game. Best-seller charts rank the Top 15 game cartridges in Billboard magazine, giving them equal status with the nation's favorite LP's. And justly so. Between the arcade Cyclopes and the home versions of video games, the industry may gross as much as $6 billion this year, according to Ronald Stringaril a vice president of Atari Corporation. At that plateau, video games will be a bigger business than the motion picture and record industries combined.

Despite the eary December 1982 panic that knocked video game stocks down by as much as 33 percent per share overnight (as happened to Warner Communications, parent company of Atari), few onlookers feel the potential of the video game business has been realized. Observers estimate that on Christmas morning 1982, there were game consoles in 14 million of the 80 million U.S. households with televisions. The Yankee Group, a Boston high-tech consulting firm, projects that by 1990 60 million U.S. households will be equipped to play video games.

Ironically, since its birth a decade ago this has been an entertainment industry without stars. Though game cartridges alone accounted for $1.5 billion in sales last year, most of the designers who write, direct, and produce these megahits labor in obscurity. Imagine the film industry if Hitchcock or Coppola were unknown, the music world if Streisand or Bernstein were anonymous, and you've got a reasonable picture of what the video game industry has been until now.

Designing a good video game is more than a token victory. The games may take only a few minutes to play, but they can take six to eight months to create, months of insomniac hours, tedium, sudden fortune, and sudden disaster. Physically, video game cartridges are nothing more than tiny flakes of melted sand jammed into cheap plastic cases. What makes them come to life, creating the little dramas that have become our new national pastime, are the instructions etched onto those silicon chips--the programming.

In the whole world just a handful of people know how to conjure a game on the screen of a home television set. New York's Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers estimates that there are only 100 video game designers in the nation. The hurdles would-be designers must pass are at least equal to those confronting other computer professionals. Designers must combine an adolescent enthusiasm for games with a disciplined understanding of microcode and an intricate knowledge of the game computer's architecture.

Microcode, a complex computer programming system, moves jittery bits of whizzing electricity through the chip on a painfully precise one-to-one basis. In one microcode game program, the shape of a castle is described as HS26263E3A2F3E. Such are the nouns of the language that directs the machine and defines the play. Every object's size, form, color, movement, trajectory, and speed must be detailed. Orchestrating a cascade of electronic impulses to the correct destinations requires hundreds of pages of formidably rigid instructions. The work is as unforgiving as brain surgery. There is no margin for error.

Nevertheless, to a certain kind of individual, the work is irresistible. The fascination of trying to get complex equipment to function just so can be enormously gripping. Steve Cartwright, who, like David Crane, is a "name" designer, describes the work as an obsession. "I'd do this even if I weren't getting paid to." There is a joy in beating the system that gives rise to an often-repeated aphorism of David Crane's. Crane's Law says that man will always use his most advanced technology to amuse himself.

The few men who can harness that technology (games design is a virtually all-male fraternity) are the creative basis of the entire industry. But one of the games companies play is awarding designers scant credit for the enormous profits squeezed out of their video games. The largest manufacturers--Atari, Mattel, and Coleco--routinely refuse to assign credit for their games. Company officials publicly maintain that all their games are produced by teamwork, so crediting an individual would be inaccurate and unfair to the rest of the team. The firms sometimes tie themselves in embarrassing knots complying with these policies. A recent issue of Intellivision News, the slick newsletter from Mattel for Intellivision owners, includes a lengthy interview with "the man who designed and programmed" the game Utopia, Nowhere in the article is the designer's identity disclosed.

|

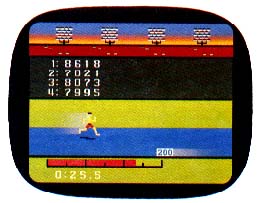

| Decathlon is Cranes newest video game on the market. |

Laboring in anonymity is quite a sore point for most designers, according to Alan Miller, who joined Atari after a stint at NASA. "When I worked at NASA and people asked me what I did, I really couldn't tell them. The nature of that kind of engineering is such that you work on small parts of a number of larger projects. But games design is different. You are creating something that is an expression of yourself. A game designer has as much right to be credited for his work as a composer." Some wily designers found ways to take public credit without their bosses' knowledge, Miller says. Two of his former Atari colleagues programmed their games to reveal their identities onscreen after a chance series of moves.

Today, through a combination of hard-won legitimate recognition and sheer industry hype, designers are entering the limelight. Even monolithic Atari, which has long suppressed designers' identities fearing personnel raids and industrial espionage, has begun to name names. The imaginative people who devise video games for a living are becoming public figures, with fan clubs and even pestering groupies. Throughout the nation, teenagers are filling mail sacks with requests for mementos from their idols: an autographed printout of Rob Fullop's data-entry routines perhaps, or a note on code-crunching tips from Carol Shaw. Many kids with personal computers are beginning to program their own games. If through repetitious play some teenagers are turned on to new professions in computer science, then the mania is worth it.

The leader in crediting designers for their creations is Activision, whose president, former recording industry executive Jim Levy, promotes his people like rock stars. The flourishing software firm was founded in 1979 by Levy, Crane, Alan Miller, Bob Whitehead, and Larry Kaplan, all disaffected Atari designers who wanted more money and recognition.

From the first, every Activision game was packed with an instruction manual carrying a photograph of its creator and a signed letter with the designer's playing tips. Activision ads also emphasized the designers' names. Levy made every effort to boost his staff in hopes they'd build a loyal following. Video gamers, the theory went, would rush out to buy the designers' new games, just as readers eagerly purchase a favorite author's latest novel.

It worked. Of 25 cartridges the company has released to date, a dozen have "gone gold," with more than half a million sales. Three have "gone platinum," breaking the million mark. Today Activision's designers receive 12,000 fan letters a week, according to vice president and editorial director Tom Lopez. Skeptics are led to Activision's highly congested mailroom to see for themselves the mountains of correspondence generated by Activision's stars.

The mailman's nemesis, the man behind Pitfall, the video game megahit of 1982, is a homespun computer virtuoso from Nappanee, Indiana: David Crane.

Crane doesn't act the part of a blue-chip success. As a founder of Activision, which has zoomed from nothing to approximately $125 million in sales in four years, he has doubtless made his first million, maybe multiples. Yet he remains remarkably unaffected by prosperity.

|

| Fishing Derby, a 2600 game from Activision. |

Crane dresses for work as if he were on the way to a softball game. Blue jeans are the designer's unofficial badge of office--the people in Activision's research lab dress more casually than the people in the mailroom--but Crane takes perverse pride in declaring that he's worn a suit "precisely three times in my adult life." He appears to be making a kind of disheveled statement about rejecting the trappings of maturity. His shoes--cheap brogues the size of gunboats--are worn to mere nubs. "These are Red Wing shoes, and, obviously," he says, raising one outlandish foot to display a dwindling heel, "I wear them until they are well used." Not because he can't find shoes in his size, he insists, but only because they're comfortable. "It's not hard to find shoes when you know where to look. I've visited my home town in Indiana twice in the last ten years, and I never fail to stop by the shoe store. The owner always has a pair for me. He keeps one pair of 15 double-A Red Wings in stock, just in case I drop by."

Nor does Crane work in a lavishly appointed lab. The designers share a little row of cubicles without doors, each designed to contain one person. Their walls don't reach the ceiling, but stand about five and a half feet high. You can look over them. Like study carrels, they create no privacy. Each has a desk with a standard-issue color TV, a computer console, and a few unclassifiable electronic gewgaws on it. A few cubicles have Activision ads or cartoons pinned to their cloth-covered steel walls. None have green houseplants or a vase of cut flowers to soften the functional feel of the place. Overall, the designers' environment looks like a rat maze designed by a tasteful behavioral psychologist.

If you are what you eat, Crane is pure junk. "I have a real rich palate," he says with his trademark smirk of amusement. "I eat virtually every meal in a sandwich shop: hamburgers, stuff like that. I am a chocolate milkshake connoisseur." His diet, a mulch of tuna sandwiches, candy, and cola that hardly seems capable of sustaining intelligent life, is a source of horrified amusement to most of his friends. Although he's a tee-totaler, he hasn't placed many other curbs on his appetite. Crane lopes through the halls of the research lab carrying a liter beer mug filled to the lip with soda, which fuels his inspiration the way absinthe fueled Oscar Wilde's. When he traveled to New York City to accept the video industry's award as best game designer of 1983, Crane indulged himself by ordering $20 worth of white chocolate pretzels. The delivery boy misunderstood and brought 20 pounds instead. Crane lit up with joy.

In all of this, he is not much different from his coworkers. Candy cravings have evolved into a standing joke around the Activision office, where everyone has a particular favorite. Alan Miller favors M&Ms in every color but brown. A typical idea meeting leaves the conference room table littered with depleted tins of Excedrin, brimming ashtrays, and half-eaten chocolate chip cookies. The entire organization seems to tremble on the brink of diabetic shock. "If there's one trait designers have in common," Crane says, "it's our taste for chocolate."

Crane favors simple pleasures after hours as well. He lives in an apartment complex he calls "a Silicon Valley microcosm," where he can quickly find a tennis partner, a bridge party, or a computer professional when the mood for a technical bull session strikes. His apartment, though less austere than his lab, is decidedly modern and functional. Everything centers around the big-screen TV that dominates the living room. A sectional sofa curves around it to accommodate friends who drop in to watch Crane's collection of laser-disc movies. An octagonal game table in the dining room is eternally set up for bridge.

Until his latest housecleaning, the spare bedroom was littered with paperback science fiction novels, newspapers, and magazines. This idea--mulch for future games blanketed the room "to the point where you couldn't tell what was going on," Crane says. "It was books everywhere. I read reams of science fiction. 'Cause, hey, sci-fi's my life, to quote Mork." Crane's mother feeds his habit, spending weekends at garage sales with a computerized list of every science fiction book in her son's collection, buying second-hand books for a dime a piece. Crane returns with boxes of them every time he visits his parents in San Diego.

Crane had little patience for books until quite recently. "I never read when I was a kid. I don't know, maybe it took too long. Now I like mostly light science fiction. I've read some social science fiction, but...," he pauses, groping for a suitable distasteful description, "it's just like the real world," he finishes, grinning.

Reading occasionally gives Crane notions that become games. So do movies; Crane recently saw the animated Disney feature The Sword and the Stone and was impressed with the climactic wizards duel. But with so much competition in the field, it's harder than ever to think up original games.

Each designer has his own particular work habits and creative techniques. Miller loves sports, hence his first two games for Activision, Ice Hockey and Tennis. Crane, who's known as a graphic virtuoso, begins by creating visual images, then building a game around them. Sometimes a premise occurs to him like lightning striking the primordial soup, and the game evolves smoothly. More often, Crane says, designing video games is a process of eliminating every idea that doesn't fit, like a sculptor chipping away at a block of marble in search of a statue trapped within.

|

| Pitfall Harry, the most popular 2600 character around. |

Occasionally, he just gets lucky. Crane was on his way to a trade show in Chicago when he saw a man trying to run across Lake Shore Drive's rush-hour traffic. "Hey, there's a good idea for a video game," he remembers thinking. It evolved into Freeway and a cartridge that went gold," selling more than half a million units. "But for how to hook everything up, the idea was there in ten minutes. That was fun," he says. "The rest was hard work."

Once he's found an idea, Crane writes a brief description of how the game is supposed to play. Then he settles down in the lab and spends days alternately studying cloud formations out the window and writing detailed computer code in brief, intense bursts.

The process that creates a challenging game can be endlessly tedious. "You're giving extremely simple instructions to the microprocessor, telling it to take this number and move it over there. That's all I can do," Crane explains. "But if I can do 30 of those in a row, in the proper sequence, I can make something pretty fancy happen."

Though the Atari VCS is a comparatively crude first-generation game console, it's the de facto standard for the industry, with more than 12 million consoles sold. Because it requires a fair amount of programming skullduggery to produce a challenging game on the VCS, Crane and his colleagues have become adept at "crunching code," or squeezing as much information as possible into small computer memories by writing a kind of programming shorthand. "I often start a game by coming up with a new way to fool the machine, and seeing what kind of a game it will become. Grand Prix is an example. It was unthinkable before that to make a car the shape and color of those in Grand Prix. At the time I was doing Grand Prix, people were telling me there was no way to pack that much information into the limited amount of memory space we had available. So I did. So there!" He beams.

As the memory chips that are the brains of the games become more sophisticated, so does Crane's job. His recent, more complex games require as many as 4,000 separate instructions, which are physically "burned" onto computer chips to provide the look and playing features of the games.

Building cartridges is not only more profitable than building the computers that run them, it requires very little overhead beyond hiring the talents of a few brilliant games designers. Because the markup is so high--the raw materials of a cartridge that retails for $30 may cost only $5--one hit can generate as much money as a blockbuster movie.

Pull apart a game cartridge and you'll find mostly air. The plastic housing, slightly larger than a deck of cards, is empty except for a couple of clips or springs securing a wafer of green circuit board veined with the silver squiggles of solder traces, electrical pathways printed directly on the board in place of insulated wires. This is the component that plugs into the game console's circuitry, summoning up mirages on the TV screen.

The snap-together cartridges are manufactured in snap-together buildings. Red Spanish tile roofs and featureless sheet concrete walls are the vogue in Milpitas, where Activision produces its cartridges: There's no aesthetic distinction there between a branch bank, a bookstore, or a taco parlor. The buildings are assembled by tilt-up construction, probably the fastest and cheapest way of erecting a building yet devised. The walls are laid out facing the base, then tilted forward into place--and presto.

"In earthquakes, the walls fall away from the foundation," says one local executive. "That sounds great, until you think where the roof goes."

Labor in Activision's factory is cleaner, but no less monotonous, than work on any other assembly line. Several short conveyor belts carry the cartridge through a series of metamorphoses. The green circuit board is taken out of stock, fitted with bumpers, and loaded with the necessary components, in this case a ROM memory chip. The chip, which has been permanently imprinted with the game program, is encased in a rectangular black "bug" joined to the board by a score of silver legs through which it can communicate with the outside world. After the ROM is loaded, the boards march through an automatic soldering machine, a rinsing and cleaning device, and a drying area.

The company delegates its manufacturing work to Selectron, a specialty sub-contractor that also assembles cartridges for Imagic and other independent cartridge builders. About 75 Hispanic men and women assemble the units, plug them momentarily into a testing console, pack them with instructions, and store the boxes for shipping. No one on the line wears surgeon's gloves or hair nets. Those precautions, used to prevent contamination of chips during their manufacture, are unnecessary at this stage of the process. A rock and roll radio station blares a background beat for the work. A sign lettered with a marking pen offers inspiration: TODAY'S GOAL IS 76,000 UNITS.

The path that led David Crane to Silicon Valley began in childhood. "David was the kid who was always up in the attic fiddling with a crystal radio set or setting fire to his bedroom with a chemistry experiment," says Activision's Levy. He was a born tinkerer, and there was always something a bit looney about his creations. Crane's grandmother likes to tell the story about the summer he got the triple sunburn. He was twelve or thirteen and burned so severely that the skin peeled three times. That summer he built a gadget with an Erector set arranged so that he could back up to it, push a panel, and have his back sprayed with sunburn ointment.

Crane's older brother dabbled in chemistry, rocket fuel, and electronics, and young David developed a taste for science by looking over his shoulder. His introduction to electronics began extracurricularly around age twelve. "I tore apart radios and things like that. I got an old used TV for my thirteenth birthday. Dad paid $40 for that TV. I wired it so I could put the picture tube up in a cabinet and keep the controls down near the bed. Never quite got that to work well. Ended up putting it back together so that I could watch it."

His passion for the screwdriver and the soldering iron grew throughout his school years, and Nappanee, a freckle on the map near South Bend, offered few distractions. (When Crane talks about his youth, he mimics the tone of a Horatio Alger story of humble beginnings and grand adventures, declaiming, "I was born and raised in a small town in northern Indiana.") The B&O railroad ran through Nappanee, but, beyond watching the trains, visiting his father's kitchen cabinet factory, or watching the wheat grow, there wasn't a great deal for a bright young man to do. The nearest town of any consequence was 40 miles away.

"We didn't have a McDonald's," Crane recalls. "Only recently have the big-name fast-food restaurants moved in. It was a pretty small town, but there was a good curriculum for electronics and computers, surprisingly. We had consolidated two school districts and therefore had a lot of money. We put together a school with a lot of brand-new stuff."

As Crane remembers it, he was always a terrifically smart kid. In high school he would ignore the textbooks, listen to the lectures, and advance from grade to grade. Though abstruse electronics commanded a lot of his attention, he was not a social misfit. He played tennis, and lettered four years. "I was not an overachiever. I just visited high school," he shrugs. But he learned to program computers in three languages and built his first computer at seventeen.

Crane graduated in 1972 and immediately entered the De Vry School of Technology in Phoenix, Arizona. It was, he says, his peak as an inventor. "If I needed anything, I'd build it." The appliances he built were not the sort most people could be said to need. He made a programmable rhythm section in 1972 when they were all but unheard of, a tic-tac-toe playing computer, using 72TTL integrated circuits ("it was a huge, monstrous box!"), and a click that could time millionths of a second between two events.

Crane required that device to hone his skills as a semi-pro Foosball player. "It was a professional hobby for a few years. There was a million dollars in prize money on the tour then. I'd cash my weekly paycheck from my electronics job to fly to some major city in the United States and play Foosball for two days, 24 hours a day. I'd occasionally win back air fare if I was lucky." He placed 64th in the nationals the first year he played.

The campus unrest of the early Seventies was at the farthest edge of his awareness. "I'm not concerned with current events," he says nonchalantly. "Anyway, I didn't attend a campus. De Vry was a two-story building that was 80 feet square, with 2,000 students. The courses lasted all morning or all afternoon. You stayed in one room and the teachers shuttled from class to class. The school went five days a week, forty-eight weeks a year, two weeks off in the summer, and two weeks off in the winter." Crane, bored with even this accelerated program, finished the four-year course in 33 months and went to work for National Semiconductor in 1975.

It was the middle of the worst recession for the electronics industry in the last decade. But National was a big company, and Crane was given carte blanche in the most profitable division, the Operational Amplifiers department, which produced a little chip that was a basic building block for a lot of circuitry. The 741, as the circuit was called, was selling by millions. Quality control for the circuits required someone to flip switches 1,024 times, while making measurements out the other end. Crane stepped in and built a computer system to do the repetitive testing.

Crane's tinkering baffled everyone at National. "The people there were not into computers. But the manager of the department knew this was the wave of the future, so he said, 'I like what you're doing. Keep it up."' Unfortunately, the only person who could run the device was Crane. And he was on his way to Atari, after a chance meeting with Alan Miller on a tennis court convinced Crane Atari was the place for a bright young engineer to be. "My last official act at National was to write up a $30,000 purchase order on a system from Hewlett-Packard to replace mine, so they'd have documentation on it telling them how it does what it does."

In late '77, Atari was the engineer's equivalent of Disneyland. "We had a lot of fun," he says. "Warner had owned it for a while, but Nolan (Bushnell, the founder of Atari and creator of Pong) was still running it. He's an engineer, and he ran the company as an engineer would run it. It wasn't making any money as an engineer would run it," Crane laughs, "and that's why Warner bought it. But he would still isolate the engineering department. He'd say, 'You guys go over there and have a lot of fun. We'll come back and talk to you every once in a while."'

Crane found ways to make the computer draw pictures on a TV screen that no one else can duplicate, but he decided within two years that he had no future at Atari. He dislikes talking about the experiences that caused him to leave. Other than to say that Atari "became too much like a big company," he prefers to keep silent.

Alan Miller, who worked closely with Crane throughout that period, is more forthcoming. He responded to an Atari help-wanted ad in a local paper when the company, preparing to introduce its VCS home video game system, urgently needed engineers to create game cartridges. Miller was to translate a moderately successful arcade game, Surround, into a home video version. He played the game in arcades, added some variations, and completed the project to everyone's satisfaction in about four months.

At Warner Communications, which had just purchased Bushnell's freewheeling organization, a number of designers became disenchanted. With the fun being squeezed out of their work, Miller and Crane grew restive. They resented a pay scale they considered below the industry average for engineers, anonymity, and supervision by people ignorant of the technical aspects of game design. "There is no way a person who's not familiar with the intricacies of an Atari 2600 VCS can assign and direct the production of games for it," Miller says with finality.

Miller, Crane, and two other Atari designers, who between them were responsible for more than half the company's cartridge sales, jumped ship to create their own software company. Activision became the first independent company producing games for the Atari VCS. Atari, needless to say, was upset, and sued the new company for $20 million, charging unfair competition and conspiracy to appropriate trade secrets. The suit was settled out of court last year. Since then, Activision has branched out, producing games for the Intellivision system. Privately held Activision now has about fifteen percent of the game-cartridge market, thanks in part to Crane's megahit Pitfall.

For adults and the few children in North America who have not seen Crane's hit game Pitfall, some explanation may be in order.

Pitfall is a race against time in a jungle setting. The player's alter ego, an animated stick figure called Pitfall Harry, runs through the wilderness, grabbing treasures, searching for shortcuts, leaping over marauding scorpions and cobra-rattlers (hybrid: snakes found only in Crane's imagination), and grabbing jungle vines to swing over alligator pits. The idea is to get out of the jungle alive, with as much gold as you can carry.

If this sounds like a metaphor for contemporary life, that may help explain the game's popularity. Pitfall owned the number one spot on Billboard's best-seller list for four months last winter, including the high-volume Christmas season. It has dropped lower in recent weeks, but it's still going strong after well over a million sales. Clubs of Pitfall enthusiasts have been organized nationwide; there are almost 5,000 members in the Detroit metropolitan area alone.

Pitfall's graphics may also help to account for its success. Anyone familiar with the screen play of Atari's Asteroids or Defender will notice that the images in Pitfall do not flicker--a common occurrence in video games that display several objects on the screen at one time. Pitfall Harry is a detailed, almost humorous figure. In fact, Pitfall Harry looked cuter to consumers than E.T., the cuddly alien who had been expected to create a Christmas gold rush for Atari.

When Steven Spielberg's film made a meteoric showing at the box office, a phalanx of manufacturers descended on his offices to bid for the video game rights. Atari won and wasted no time in bringing its E.T. game to the home screen for Christmas. Implementing a special rapid production plan, the game was conceived, the program written, and the cartridges manufactured in a whirlwind sixteen weeks, a quarter of the time the process typically takes. Haste apparently made waste, however, because the game never made Billboard's Top 15. Madeline Gordon, general manager of San Jose's Microsel Distributing, Inc., said the game was a disaster for Atari. "I cancelled 15,000 (E.T.) pieces from Atari. It wasn't selling," she says.

To prevent similar debacles, Activision gives its designers a flexible work schedule many top executives might envy. The industry's short product cycles lend to many projects an atmosphere of crisis, so that the programming, which is intense work at best, becomes arduous. Without generous allowances for rest and, recreation, designers can succumb to a long-term tiredness that spoils their work. Throughout the writing of the game program, a procedure that may take a year, they are usually unburdened by deadlines. "Some designers get writer's block, and they don't show up to work for a day or two at a time," says Levy. "But when they get an inspiration, they can work for hours on end."

Ideally, Levy continues, designers should be freed of as many distractions "as a rational world can allow." It's necessary to concentrate," says Crane. "When you do a video game, you have to keep a thousand different details in your brain at once to be sure everything's going to work when you get done. And any interruption will make you have to start over." To that end, the telephones in the design lab flicker a light, rather than ringing, to signal incoming calls. A polite but firm receptionist rebuffs virtually every attempt to communicate beyond the locked lab door, not even company memos circulate there. Less than ten non-designers have access to the lab, and the entire area has been made off limits to smokers. Even top management pales at the thought of intruding, let alone rushing the designers.

No one calls this pampering. It's just another example of the firm's benevolent paternalism. Levy takes pleasure in rewarding his people. A year ago, after Activision more than doubled its staff, Levy noticed that people weren't taking time to chat in the halls. To encourage the employees to get to know each other, he flew the entire company to Hawaii for a week, a trip a local travel agent estimated cost more than $100,000. In such an organization, nobody cracks a whip over the creative staff.

"Time pressure makes the designer take short cuts," says sympathetic editorial director Tom Lopez. "It could turn a megahit into an average game."

Crane wouldn't know a time clock if he hit his head on one. "I get up at least by ten or ten-thirty every morning," he says with an expression just short of gloating. "If I've played a lot of tennis the night before, I'll sleep an extra hour just to rest my bones. I go into work about eleven, just in time to make the lunch crowd. Then I'll work through the afternoon, and, if it's a nice day, I'll go home to play tennis. While I'm waiting for a tennis court, I'll play video games.

"I could probably disappear for two or three days and nobody'd know I was gone. Eventually we have to have a little group approval on our games, when the other designers pass judgment, but a lot of it can be done by one person sitting alone at home. Some of the people will sit at home in a rocking chair writing code on paper for three solid days." The only way some people know he's at work, he says, is to look in the parking lot for the BMW with the personalized PITFALL license plates.

Nevertheless, Crane is the firm's most prolific designer. According to his coworkers, Crane is to programming what Evelyn Wood is to reading. He sits before a computer terminal, fixes its screen in a tunnelvision stare, and types in ten-minute bursts of pure microcode. Then he walks away and sips at his immense cola mug for a long time before returning for another ten-minute blitz. In those few minutes he accomplishes as much as other people might in an hour. He can bang out a finished game in three months, a speed few can equal.

"It's pretty intensive work. That's why I only do it a couple of hours every day. Because you've got to keep every little aspect of that circuit in your mind," he says.

Like obsessive authors who spend afternoons fretting over a comma, designers spend hundreds of hours polishing their games after most people would say it's done. "The last hundred hours are spent on details you might never notice," says Crane, holding his thumb and forefinger a hair apart. "Unbelievably teeny differences. Like in Pitfall, I made it easier for the guy to jump from a standing start. Originally you'd have to hit the joystick and the fire button right at the same time. Now, if you don't, the logic takes care of it. Just thinking about it, coming up with the idea and deciding to do it and getting it right took about a week. But it was a very important aspect of the game, making it play right."

Still, even an experienced designer hits a fair share of dead ends. Crane estimates that 40 percent of his ideas go nowhere. "I have at least half a dozen almost finished games that just weren't good enough. I've come back to one three times. I'm still going back to it because it's one of those games that feels like it ought to work. But I can't find out why it won't. Every game is different. Some don't have enough aspects of play, enough details; every time we trash one, the reason is different."

The qualities that make a good game are simple: "If it's fun for a half-dozen video game designers to play, it's a good game."

Today Crane is a celebrity of sorts. It seems only a matter of time before he appears on television brandishing an American Express card and asking, "Do you know my name?" Yet he doesn't consider himself a particularly noteworthy fellow. "There are a lot of people who like to play my games," he says with an aw-shucks smile. "They like to tell us that, and I like to hear that. It's always good to have recognition for work well done."

Mister Smith goes to Silicon Valley. It's the stuff of an uplifting Frank Capra movie. "I feel happy," he says, stretching his basketball player's legs contentedly. "I'm having a lot of fun. But I'd be enjoying myself no matter what I was doing, because I'd only be doing what I was enjoying.

They used to hang people for having this much fun.

Colin Covert writes for the Detroit Free Press and is a contributing editor of Ambassador Magazine.