Interactive Text In An Animated Age

Infocom Faces The Challenge

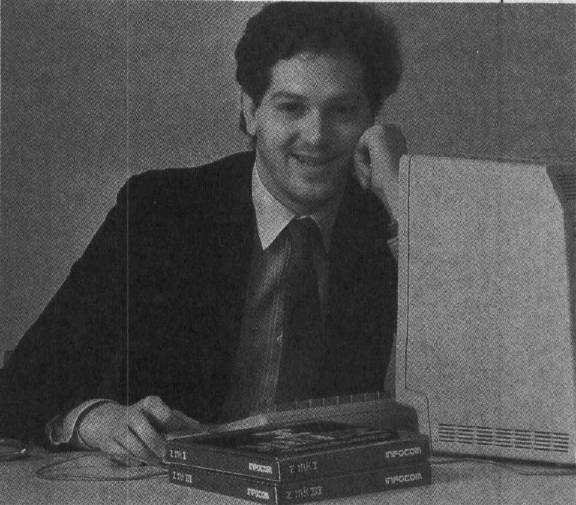

A Conversation With Joel Berez And Marc Blank

Keith Ferrell Features Editor

Infocom has ridden through a decade's worth of changes in the computer industry by concentrating on one type of product: interactive fiction. The Zork Trilogy has sold more than a million copies. Other best sellers include The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Planetfall, and Leather Goddesses of Phobos.

Now a wholly owned subsidiary of Activision, Infocom continues to focus on interactive fiction. We were curious about how the market for text adventures was holding up in a marketplace that's more and more graphics-oriented—and where is interactive fiction headed?

COMPUTE!: It seems that increasing emphasis is being placed on graphics and animation in discussions of computer games and entertainment. How does a text-oriented publisher compete with this trend?

Berez: It's true that most people think of graphics when they hear the phrase computer game. It's been true for years, though.

You're in a hotel room, armed with a tape recorder and stack of notes. Judging from the view, that's Cambridge, Massachusetts, outside. MIT sprawls around your hotel, the university's varied architecture centered, it seems, around a huge dome. Being here, you can't help but think how many facets of computer technology have been shaped here. From mainframes to micros, this is the East Coast center of the computer industry.

Perhaps most important of all, at least for immediate purposes, this is where Zork was born. And that's why you're here.

You're not alone in the room. Two men are with you, both eager to talk. One is Joel Berez, president and founder of Infocom. The other is Marc Blank, a member of the original Infocom team, co-author of Zork, and lately a free-lance developer and consultant. Blank's latest piece of interactive fiction, Border Zone was published by Berez and Infocom late in 1987.

After a moment's orientation, you begin the questioning.

Blank: In fact, most people use the terms interchangeably, especially people who aren't computer owners—they say video games when they mean computer games.

Berez: In the early days, people saw arcade games before they ever saw a computer. Naturally, when they saw a computer game, they immediately thought it was the same kind of thing translated to a computer.

At Infocom, we've always tried to sell the concept of interactive text-only products.

COMPUTE!: The word interactive itself has lately been co-opted by manufacturers of VCR games, among other things. How do you position interactive fiction in an entertainment marketplace like this?

Berez: If you look at the entire marketplace and divide it up, there are arcade games, sports games, simulations, and stories.

Stories are actually a very large segment of the market—perhaps even a quarter of it right now. Story products in general do not have fast-action graphics of the sort that people are used to. Certainly interactive fiction rarely has graphics at all, and even fantasy role-playing games tend to have fairly simple graphics.

So the people who are attracted to the story category tend to discover that graphics and action aren't everything, and aren't necessary for enjoyable games.

Blank: In fact, there are very few graphics adventures in which the graphics even play an integral part in the story or provide any information that couldn't be provided otherwise. Rather than try to make the stories more complex, the easiest thing to do is to make the product look nicer—to add bells and whistles.

This has been going on for a while. Back in 1981 and 1982, we were told by distributors that we were crazy. Nobody wanted text games any more, we were told, because machines were all becoming graphics machines.

So this [trend toward graphics] isn't anything new. The graphics keep getting better on the machines, so it's not surprising that some people say text is dead.

But for people who like stories, text adventures have just done a better job of telling stories. That's the important point.

COMPUTE!: With a market increasingly accustomed to graphics adventures, however successful or not, where does Infocom find new customers?

Berez: In some ways, it's easy to convert people from, say, fantasy role-playing games to text adventures, because they're already into that sort of thing.

But it's been a challenge for years to attract people from other categories. We find that we can get a reasonably high conversion rate if we can get people to sit down at a computer and try one of our games for a while.

COMPUTE!: Sophisticated graphics capability is being emphasized by the computer manufacturers as well. What sort of response are you getting from the higher end graphics machines such as the Amiga?

Berez: We've just done a graph of our sales over the last year to see what our penetration is. Our number-one machine is the Macintosh. Number two is a tie between MS-DOS and Amiga. After that come Atari ST, Commodore, and Atari XE.

It turns out that there's no noticeable correlation between graphics machines and our penetration. There is a high correlation between the price of the machine and our sales. We do better on the expensive machines than on the inexpensive machines. People who are putting more money into their machines tend to buy more of our software.

COMPUTE!: Is advertising an effective means of gathering new customers?

Berez: We've tried a number of approaches with good results. One ad had the headline, "We stick our graphics where the sun don't shine!"—with an illustration of a brain. Another ad showed a typical computer alien from outer space, with the line, "Would you pay a thousand dollars to match wits with this?"

Blank: The point was that you should be able to expect more from a story than just getting a little animated character to move around on your computer. These are very powerful machines, and they're not really being used to their potential—at least in the storytelling realm.

What Infocom has done from the start is to simulate a universe and then tell a story within that universe.

COMPUTE!: It's an approach that has evolved over the years, while retaining consistent goals.

Blank: Yes. Every game has had some level of improvement. It's gotten more sophisticated, smoother; the interaction has gotten better.

But in the long run, as things progress and more of a mass market grows, you'll be reaching more people who look for story. People are used to storytelling from other media, whether it's music, or movies, or books. People look for stories. That's what sells books; it's what sells movies.

There's more than just special effects. A lot of people thought after the Star Wars movies all you had to do was put in some fancy special effects. But if the movie was junk, and the story wasn't good and didn't pull you in, the special effects alone weren't enough.

My sense is that the best thing to be doing is honing skills for telling stories interactively, and not wasting time on graphics technology that is going to be outdated anyway. In the long run, none of these technologies are what consumers are ultimately going to want. But they are going to be interested in some kind of interactive storytelling, whether through text or animation.

COMPUTE!: Do you face any problems as a result of the decline in literacy? Are Infocom's sales touched by the fact that people don't seem to be reading as much as they used to?

Berez: Our audience tends to be composed of heavy readers. We sell to the minority that does read. And there's still a good, solid core of people who do read.

Blank: Part of the trend can be traced to immediate gratification—TV, and so on. There's some relationship, but I think the people who really like stories will still be attracted to interactive fiction. One of the things Infocom has been doing lately in a few stories is trying to make it easier for people, trying to provide more of a short-story feel. We're putting together games now that people can play for a while and then put down, having gotten a good and complete experience out of the game. Then they can pick up the game later and have another experience with it, and so on.

COMPUTE!: So you're willing to relax the format a bit.

Berez: For a long time we were real purists. Because everything was in the user's imagination, and the games were enjoyable the way we were producing them, we never felt any need to add a little sizzle, or to snazz up the interface.

Right now, though, we're experimenting with a lot of things to make the games a little easier to play. We're looking at ways to improve the interface, to make it easier for current users and, frankly, to try to get new people to try our products and give them a chance.

If the screen is more visually interesting, it's more likely that somebody who would not have attempted to play one of these games will actually try it.

COMPUTE!: What has been the response from your existing customers?

Blank: It doesn't detract at all from the game. It's just another way of reaching a group of people who might not feel that they were in the audience. We've always found that the important thing is for the consumer to give our products a trial run. We know consumers can get hooked on these things, but you have to overcome those barriers: "It's too long; it's going to be too hard; it doesn't look like games I'm used to."

We can address all of that without detracting from the quality of the interactive experience.

Berez: For example, in Beyond Zork, because people are tired of drawing their own maps for our games, we've included an automatic onscreen mapping facility.

COMPUTE!: Why now? What made you decide it was time to enhance the interface and add other effects?

Berez: One reason we're much more open now to experimenting with other kinds of effects, including sound and graphics, is that machines have gotten to the point where they're powerful enough for us that we can give you the whole experience and add something to it. A few years back, we would have had to compromise the interactive experience to add anything else.

COMPUTE!: So the charges that Infocom hates graphics aren't accurate?

Blank: Not at all! All we've ever said was that what's important is the story. The way you tell the story, and the way that story interacts within the user's imagination is very powerful. You don't need graphics.

But we all like graphics games, too. It's a different type of experience. An all-text Pac-Man never made sense: Eat dot. Wokka.

COMPUTE!: Is there a point in interactive fiction, though, at which added effects become obtrusive?

Berez: This is experimentation, and if something doesn't work so well, it won't be continued. In Beyond Zork, you can turn the new features off if you don't care for them.

COMPUTE!: Marc, you've said that all the features are subordinated to storytelling. How far can you go with this? Are we moving toward a new art form that merges the storytelling of fiction with the puzzle approach that has typified text adventures? How do you approach these questions when writing a new game?

Blank: I've just finished a new game, Border Zone, and my goal in writing it was to make it a storytelling experience. The story is very important—there are puzzles, of course, but the puzzles are so embedded in what's happening in the story itself that you almost forget that they're puzzles you're doing. It's an intrigue game, with three different scenarios, and you're a different character in each scenario. Also, I've added real-time to the game.

COMPUTE!: Tell us about that.

Blank: In a game of intrigue and suspense, where you want people to feel that sense that things are happening all around them, that they're trapped and they have to get out, being able to use realtime is very effective. There's one point where you have to set a fuse on a bomb to go off in a certain number of minutes. Once you do that, it starts ticking. No matter what else you're doing in the game, you're aware that bomb is getting closer and closer to detonating.

What's important about these extra elements is using ones that are appropriate. It's not something just tacked on as a bell and whistle—it's an integral part of the story.

COMPUTE!: You're seeking ways to make the problem-solving and puzzle elements serve the cause of narrative.

Blank: Yes. Stories have a sense of time and progression and dramatic thrust that's hard to achieve in this medium. But we are constantly experimenting, and getting closer to real fictional experiences.

Berez: These are a form of literature, but you can't just translate a book into a computer game. There has to be some advantage to using the computer, or the user would be better off reading a book.

In the early days, the advantage was the feeling that you are there. The puzzles added to that—they gave you reasons for interacting with the environment we put you in.

Now we're experimenting with other approaches that may in fact feel much less puzzle-oriented. They may actually be much less puzzle-oriented. But you'll still be drawn through the story. You'll get a certain feeling that you wouldn't get just reading a book.

COMPUTE!: Zork came out of mainframes. You've found great success in the micro market. What about the next generation of computer technology? Can we look for Compact Disc-Interactive (CD-I) games from Infocom?

Berez: What we do is interactive storytelling, and that implies that we'll do things for any medium that can be interactive. We've produced books. CD-I is definitely something we want to work on.

COMPUTE!: What form might an interactive CD-I take?

Berez: Audio is a particularly good medium for translating Infocom games. Listening uses your imagination. The key, though, is to use sound, or any enhancements, the same way we use text—as something that adds to the imaginative experience.