Modern Memory: The Future Of Storage Devices

Selby Bateman, Assistant Editor, Features

Big business is already using microfloppies, Winchester discs, and laser technology for data storage. As some of these innovations filter down to the home computer market, your tape recorder could become as obsolete as a paper tape punch.

Linda Helgerson was up to her ears in floppy discs. Something had to be done. Three or four hundred of the 5¼-inch discs were stored in her home—row upon row of mailing lists, biblio-graphical data, and spreadsheet analyses.

"I just didn't have enough storage. My mailing list itself was on five floppies that had to be merged," says Helgerson. "There's just no way I could manage that amount of data using floppies."

After a careful study of her needs, she purchased a 10-megabyte hard disc drive. The result has been dramatic. Since she put her mailing list on the hard disc system, she has added another 6000 names, and there's still plenty of room to spare.

Mass Storage Isn't For Everyone

As head of her own northern Virginia consulting company, which is run out of her home, Helgerson admittedly has extraordinary storage needs. The two TRS-80 Model 3 computers which serve her business, Quarry Hill, Inc., also double as teaching tools, game machines, and word processors for her two teenage daughters.

Helgerson is one of a growing minority of personal computer users who are finding that their needs are not met by minifloppy disc or cassette tape storage systems. Newer, faster, larger-capacity storage devices aren't yet available for home computer users. But industry observers are seeing the first real stirrings of interest in those products among the more adventurous home computer owners.

Whether you need a different storage system now or not, it's worth knowing about perpendicular recording, microfloppy discs, interactive videodiscs, and Winchester disc drives. They'll be increasingly important to future home computing.

First, The Bad News

For those who have mass storage needs like Linda Helgerson's or who are dedicated computer hackers itching to use the latest technological innovations, there is some bad news and some good news.

The bad news, says Jim Porter, editor of the respected annual market study Disk/Trend Report, is that advances like microfloppy discs and inexpensive hard discs for the home market are at best several years away. And even then, Porter is doubtful there will be a large enough body of computer users who will want the products.

The good news, he adds, is that somebody somewhere is probably working right now on the product you want. "I really think in the small computer area almost every whim will be responded to. And if something has a following there, then the response will be fairly prompt. I've seen it over and over again. It's hard to see how any niche will not be checked out."

Before we look at some of the most important trends in storage, consider where 99 percent of us are today.

Tape Or Disc Most Common

Virtually all home computer users now have either a tape drive system or a floppy disc drive. Both of these devices use a magnetic coating that records the electronic signal from a computer. When you tell the computer to store something on either tape or disc, it writes on the magnetic medium by magnetizing small areas in a form of binary notation, magnetic ones and zeros. Once these areas are magnetized, they have a self-locking mechanism which preserves the integrity of the stored information.

As computer owners quickly find out, a tape recorder is the least expensive memory storage device. But what you save in money you pay for in time. In order to find something, the tape must physically pass in front of the stationary read-write head so the recorder can check each byte of data, in a sequential search.

Computer users did not relish waiting while the tape drive did its work, and that led to the introduction of disc drives for home use.

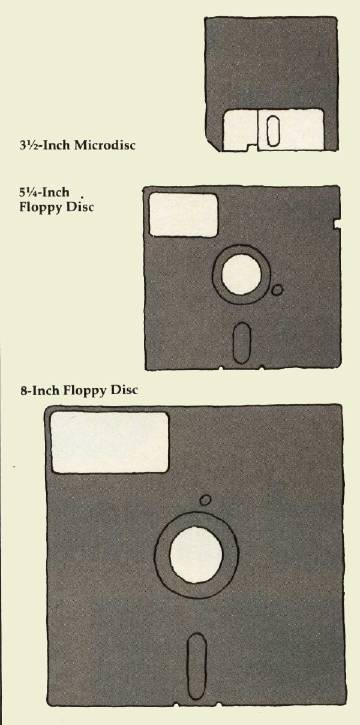

First developed by IBM in 1965 in an 8-inch format, then adapted by Shugart in 1976 to the familiar 5¼-inch size, floppy discs have quickly become the medium of choice for microcomputer data storage. The floppy disc (or diskette) is a random access device, in which both the read/write head and the disc move. In its protective paper sleeve, the disc is inserted into a disc drive, where it spins at about 300 revolutions per minute while the head seeks out the requested information anywhere on the surface of the disc.

Hard Choices

A typical 5¼-inch minifloppy disc might contain as much as 350-400K (kilobytes, or 358,400-409,600 characters) if the tracks on which information is stored are on both sides of the disc and densely packed. Many 5¼-inch discs are single-sided, single-density, and hold about half that much.

Compare that to the hard disc drive, often called a Winchester drive, which Linda Helgerson purchased. Storage capacity for that drive is 10Mb (10 megabytes, more than 10 million characters) of data.

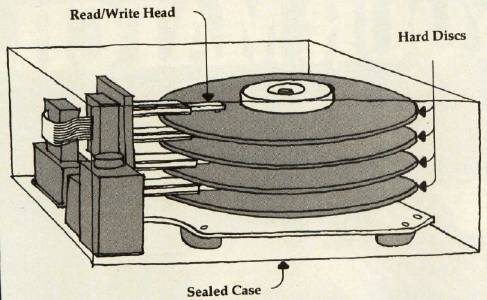

Hard disc drives cost more (Helgerson's was close to $2000) and have been used almost exclusively in business settings, where large quantities of information must be stored and retrieved quickly. As their name implies, hard discs are rigid. They are made of aluminum (also in 8-inch and 5¼-inch sizes) and are permanently sealed inside a case. Although some hard discs can be removed from the drive, most cannot. The hard disc spins at faster speeds (usually 3600 rpm) than a floppy, and the read/write head actually floats just above the disc rather than directly contacting it as with floppies. Hard discs also have faster access times.

More Interest Than Need

Why not use a hard disc for your home computer?

"We've had more than just casual inquiries about hard discs for the Atari 800," says Bob Gerwer, vice president of marketing for Percom Data of Dallas, Texas. "The people who originally bought the 800 were genuine hackers. And the ones who bought it for four or five hundred bucks have got a lot invested in it. Now, some of those people are interested in hard discs."

Kevin Burr, director of communications for Shugart, a company that has been a leader in the original equipment manufacturing (OEM) industry, reports that his organization has also seen some limited interest in hard disc drives for the home market.

"But it's not a dramatic increase of interest," he cautions. "A home user typically does not need that kind of capacity. I think it's more of a novelty rather than a strong need from those users."

Hard Discs More Delicate

At the Tandon Corporation, which during 1983 reportedly had about a 60 percent market share of the $4.3 million 5¼-inch floppy disc drive industry, marketing manager Bob Abraham concurs with Burr about the immediate future of hard discs in the home.

"The hard disc just doesn't lend itself to the home environment. I think the industry as a whole has to learn and to educate the user about the care and feeding and handling of hard disc systems. It's really a very different ball game."

One of the problems with a hard disc system for home use is that since the head floats just above the disc, it jars easily and is susceptible to crashes. When a floating head is only .0001 of an inch from a disc, a human hair takes on the dimensions of a felled sequoia. Even a puff of smoke could cause a head crash.

"I guess I would have to say that in the long term, there will be ruggedness built-in. The drives will be well-protected and shock-mounted," says Abraham. "And to a large extent, there will be a greater degree of user education. People will just learn that they'll have to be a little more careful with those kinds of things."

Microfloppies For The Home

While industry observers are less than optimistic about the future of hard discs in the home, that is not the case for the microfloppy disc.

"There's a great deal of movement in the industry toward smaller devices that won't sacrifice performance," says Tandon's Abraham.

Adds Shugart's Kevin Burr, "The home market is going to be the key audience for the microfloppy. That's why it was developed."

Microfloppies, floppy discs either 3, 3¼, or 3½ inches in diameter, have been a hotly debated topic in the microcomputer industry for several years. Disagreements center not on whether microfloppies are a good idea, but on what size should be standard. The question is still open, but the 3½-inch microdisc appears to have an edge.

A Standard Is Emerging

"We feel the standard has now been reached, particularly with the recent signing of Apple and Gavilan in a 3½-inch format," says Burr. "And IBM is rumored to be following suit.

"It is probably already the de facto standard in terms of volume and production. Shugart and Sony are the only two manufacturers currently shipping products in volume. We have a lot more products out there than anybody else."

By the end of 1983, Shugart alone expects to have shipped about 10,000 microfloppy products.

Several Advantages

There are several reasons why microdiscs are attractive for home computer data storage. Because of the ability to pack data magnetically in a more compact area, microfloppies can already equal the storage capacities of 5¼-inch or even 8-inch discs. They are less susceptible to temperature and humidity changes and, when packaged in hard plastic-and-metal casings, are less prone to damage. They are particularly suited for use in portable computers where space is at a premium.

While the question of a standard size and available software for the microdiscs may hold back "development slightly, there is every indication that microdiscs are on the way to the home. But how soon?

"There will be only a gradual build-up in the total number of microfloppies shipped," cautions industry analyst Jim Porter. "And as for their use with the home computer, for the next several years microfloppy drives are not likely to be lower in cost than equivalent quantities of minifloppy drives."

Vertical Recording Devices

Advances in magnetic media technology will also help to prepare the way for microfloppies. One of the most promising new developments is in perpendicular, or vertical, recording.

Significant increases in storage capacity can be achieved by aligning the magnetic particles on a disc in a vertical pattern rather than in the longitudinal arrangement presently used. While proponents of vertical recording maintain that products will be on the market within the next year, how soon can owners of home computers expect to find them in stores?

"You're not likely to see perpendicular recording used in products in the home for quite a while," says Jim Porter. "It's probable that flexible disc drives using perpendicular recordings will be shipped by early 1985 in limited quantities. But they'll be the furthest thing from mainstream. There will not be many producers, and the technology is likely to be fussy for quite a while. It probably will end up mainstream, but I think you should be thinking in terms of the end of the decade."

One of the leaders in vertical recording is the Minnesota-based firm, Vertimag Systems. Later this year, the company plans to market a vertical recording system with over six and a half mega-bytes per 5¼-inch disc. "We're just at the beginning of this technology," says a Vertimag spokesperson. "Just imagine what it will be five or ten years from now."

Although there are very few American companies in the perpendicular recording field, the Toshiba Corporation of Japan is expected to market a vertical recording system, probably sometime in 1985.

An Interactive Dragon On Videodisc

Last year while on a trip, Kent Wood, who directs the Videodisc Innovations Project at Utah State University, glanced into a videogame arcade and saw most of the machines deserted. Around one of the consoles, however, stood a crowd of people watching a new game called Dragon's Lair. With color video quality far superior to the surrounding games, Dragon's Lair offered 38 short action-adventure scenes with a total of 200 different decisions confronting the player before victory could be achieved.

The crowd around the machine that day didn't surprise Wood. The colorful animated game is based on a Pioneer PR-7820 interactive videodisc system. About 14 minutes of the 30-minute capacity of Dragon's Lair is interactive. That is, decisions that a player makes cause the laser beam that reads data off the disc to jump to different positions on the disc itself.

Wood doesn't believe he saw just a crowd around a game machine that day. He believes he saw the future. The next step will be low-cost videodisc systems that will be brought into homes as peripherals for personal computers as well as part of overall home information and entertainment centers.

But first, he says, people must have a greater understanding of the possibilities.

"As the level of sophistication increases in the home market about the potential of interactive video, it will overcome the people limitation. When we compare 1984 with what we had when we started in 1977 and 1978, the technology has advanced remarkably. And it will continue, though not quite as fast."

Reading The Pits

One of the most promising forms of videodisc technology is optical recording. A laser writes on the disc by burning tiny pits into the surface. A second laser then reads the pits. No head comes in contact with the disc, so wear is reduced. And videodiscs can hold immense amounts of information, say, 4000 megabytes (4 gigabytes, more than 4 billion bytes). An entire set of encyclopedias can be put on a videodisc.

But to be truly interactive, a videodisc must be able to withstand repeated rewritings, just as magnetic disks do. In burning a pit into the surface of a videodisc, however, the laser eats away some of the material.

Magneto-opticals is one of the possible solutions.

Erasing With A Laser

In magneto-opticals, the laser is used to heat a special coating until it reaches the Curie point (named for Madame Curie), the temperature at which magnetic materials revert to a neutral magnetic orientation. Information is added or erased in this manner. A second, weaker laser, using a polarized filter, then reads the materials. Wedding the laser to magnetic media in this way means vastly reduced wear on the videodisc and allows repeated rewritings.

"It's a strange kind of marriage between optical technology and magnetic technology," says Porter. "Many companies have been working in the area, such as IBM, Phillips, Xerox, and several Japanese companies."

While magneto-opticals and another laser-writing experiment called phase-change have been demonstrated in the laboratory, Porter says there are quite a few difficulties in making them producible. Commercial products using either technology are at least several years away.

Videodisc For The Commodore 64

Videodisc systems are being used on a growing basis with computers for job training, education, and data base archives. There are a number of compatible systems currently being marketed, but they can be expensive.

For owners of Commodore 64 computers who want to go interactive, Micro-Ed, Incorporated of Minnesota offers a product called Lasersoft, an interactive videodisc microcomputer instructional system aimed at the low-end market.

The system is designed to work with a Commodore 64 with 1541 disc drive, a color monitor, Pioneer 8210 videodisc player, and the Micro-Ed controller box, which links the computer and the videodisc player. The company plans to make the controller box available for other computers as well.

Marketed at under $200, the controller box enables the computer to access at random any of the thousands of frames on the videodisc and present them on the monitor. (Micro-Ed, Incorporated, P.O. Box 444005, Eden Prairie, MN 55344, (612) 944-8750.)

LaserDisc Interface For Apple

Another company, Anthro-Digital, Inc., offers a $275 Omniscan LaserDisc interface which connects an Apple computer to a Pioneer, Sylvania, or Magnavox LaserDisc. Omniscan allows the computer to duplicate the functions of the videodisc control panel, but under programmed control. (Anthro-Digital, Inc., P.O. Box 1385, Pittsfield, MA 01202, (413) 448-8278.)

Judith Paris, who edits the quarterly trade publication Videodisc/Videotex, believes that the increase in use of videodisc players as microcomputer peripherals depends on the availability of inexpensive generic interfaces and software to control the videodisc player.

She estimates that by the end of the 1980s, government agencies and the armed forces will often be using interactive video systems for archival purposes and training devices. Increasingly, large companies are moving to more sophisticated use of integrated information systems with interactive video.

A Solid Market Base

"The videodisc industry is still in search of its identity," says Paris. "But the fact that government is pushing it, and that business systems are developing a lot of uses that will have an impact on home use, means that it will really start coming into its place."

Jim Porter agrees. "There are companies putting together hardware using videodiscs and computers for business to make data bases, store digitalized material for character-by-character retrieval, and sometimes for the creation of images. These include a lot of training areas and management functions.

"I really doubt that there's much real demand to have, say, the Encyclopaedia Britannica available on your personal computer. It's going to take a lot of experimentation and entrepreneurial effort to find out just what people will want to buy."

A Cloudy Crystal Ball?

In forecasting computer industry trends, the future must often be measured in months, not years or decades. That can turn even the best crystal ball cloudy. As Porter notes, in the free-market competition of the microcomputer field, anything can happen.

"So-called predictive research is usually not worth the powder to blow it up," he says. "When someone is asked to put up money to buy some specific thing and then that individual establishes his own priorities as to where he's going to spend his money, that's a lot different from saying 'Would you like to have….?' in a questionnaire."

Personal computer owners should have plenty of opportunity to show what they do and don't want in the field of mass storage devices, he concludes. "There are literally hundreds of small operations out there that will do these things. And if they've got what people want, it'll blossom."