NONVIOLENT GAMES

Kathy Yakal, Editorial Assistant

The violence that is inherent in many of today's video games is disturbing to some people. Others don't see it as a negative influence; they stress the positive aspects of playing and programming video games. In this article, we explore both sides of this controversial issue, and look at some software designers who are providing alternatives to typical arcade games.

VIDEO GAMES (see Murder)

This entry can be found in The New York Times Index for January 1–16, 1983. The article alluded to is a small item in the January 9 Times about a high school senior in Dallas who was "shot to death in the parking lot of an arcade after a quarrel over 75 cents worth of video display games."

It's not so unusual anymore to hear about someone being killed over something rather trivial. But what might make this act of violence significant to some people is its relationship to video games.

Video games embody competition. In order to win (and it's a temporary victory), you have to shoot down spaceships or gobble up something or rescue creatures in peril. Meanwhile, someone or something is always after you, trying to destroy you.

Does this mean that a long afternoon at the Asteroids machine will make you want to inflict bodily harm on the first person who gives you a funny look? Some studies have shown that a person's blood pressure will rise and pulse quicken after playing video games. But can't the same thing happen when you're up to bat in the big Softball game or trying to meet an impossible deadline at work or even watching a frightening movie?

Game As Villain

The 1969 rock opera Tommy, by The Who, is the story of a young deaf, dumb, and blind boy who is a champion at the pinball machines. He becomes a cult hero as a result of that and, after he regains his senses later in the story, is worshipped by devoted followers who try to emulate his pinball wizardry.

If Tommy were written today, we might be humming along to "Pac-Man Wizard," instead of "Pinball Wizard." Ever since the introduction of Atari's Pong game in 1972 and the ensuing evolution of the video arcade game, these high-tech pinball machines have been showing up in cameo roles in movies and television. And they're usually the bad guys.

In this year's The Star Chamber, lawyer Michael Douglas can't even get a "Hi, Dad " from the kids because they won't turn away from their home video game. A fight over an arcade game that causes television interference in a restaurant gets a young woman involved with a young boy who does nasty things to people he doesn't like in TwilightZone: The Movie. And WarGames follows the activities of a teenager who almost instigates World War III by tapping into the national defense system with a home computer, a modem, and some big floppy disks. Worse than that, he's flunking biology.

It's not just the computers themselves that are shown in a less-than-positive light. The player's involvement with the computer or arcade game, as portrayed by movie makers, usually points out some kind of character flaw that is intensified by his obsession with these high-tech villains.

Movies may not be the best way to gauge a society's attitudes, but they often reflect sources of conflict which are easily identifiable. And video games certainly seem to be that right now. You might be hard pressed to find a young person who doesn't have an opinion about Donkey Kong, or who couldn't at least hum the theme song.

Teaching Disassociation

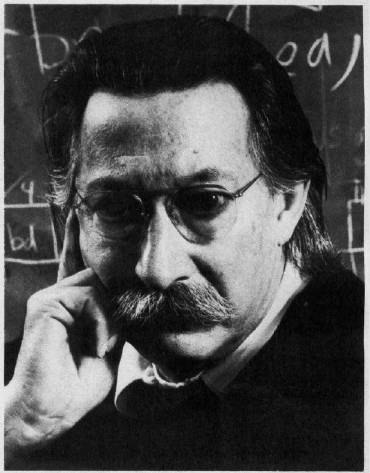

There does seem to be a degree of backlash against video games. Joseph Weizenbaum, author of Computer Power and Human Reason and Professor of Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has an explanation for why the back-lash exists. "The video arcade is the modern version of the pool hall. Some people are opposed to them for the same reasons they opposed pool halls. This reasoning is not relevant, and it masks other things that are much more important.

"It's just as Marshall McLuhan predicted: the next medium takes aspects of the previous medium. In this case, video games have taken the worst of television: its mindless violence, which is expressed in all the shoot-em-ups." Weizenbaum cites the television show "Knight Rider" as an example. "It's not that that one is exceptionally violent. It just exaggerates the cartoon-type violence."

Then why don't parents get as upset over cartoons as they do video games? Weizenbaum doesn't know. "It's the same thing you see during the week on regular TV shows. Only the television acts as babysitter on Saturday mornings," he says.

Some people claim that, even though video games may be as violent as television, they are more interactive. "The advertising claim for video games is that you can actually participate. But what is it that you're actually participating in? Killing. You can't win—all you can do is survive longer than anyone else."

Weizenbaum's chief criticism is that what's being practiced in video games is disassociation. "Video games encourage you to believe that there is no relationship between what you are doing and the ultimate victim of that action. The crucial thing is that these are lessons in what it is necessary to do in order to survive in this society. In some sense, that's really the social purpose.

"It's like women working in a bomb factory. If they couldn't disassociate themselves from what they were doing, if they were really aware of what they were actually doing, they couldn't do it," says Weizenbaum. "The same thing applies to students and teachers who believe that artificial intelligence is possible. It's very necessary in this society to render a great many things abstract, to take them out of context."

Because of this, he believes, the video arcade is a "necessary and useful training ground. The video game is not the cause of this societal trait; it is a reflection of what our society is. It would be a mistake to yell and storm at the reflection."

Lack Of Creativity

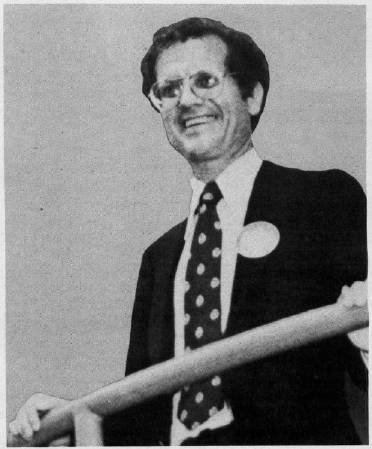

Christopher Cerf has been entertaining children for a long time. He founded the nonbroadcast division of Sesame Street in 1970, and has written music and lyrics for the television show. Since the introduction of microcomputers, he has been developing ways of educating and entertaining kids With them; Cerf and Jim Henson of Muppet fame created the video game version of The Dark Crystal for Sierra On-Line.

Cerf also developed the original concept of Sesame Place, parks near Dallas and Philadelphia which house computer centers where children can learn to use micros.

And he doesn't believe that kids are being deeply affected by the violence in video games. "I'm certainly not pro-violence," Cerf says. "I don't want to put it in games that I work on. But I think people greatly overestimate the horrible dangers of video games. Unless a child is greatly disturbed in some other way, I don't think he's going to go out and kill someone after playing a game of Space Invaders.

"I'm not denying that we don't all have some sort of aggressive instinct. Look at the way dogs will have mock fights—not really hurt each other, but just play. If the violence in a game is silly, it's just as good to play.

"Any medium that comes along has a reaction like this. Look at how horrified parents used to be that their children were wasting their quarters in movie theaters. And in the fifties, it was comic books. Doing anything in excess is a problem. You need to try to see it in perspective."

Cerf believes that resorting to extreme violence in a video game indicates a lack of creativity on the programmer's part. "I was appalled by the violence in Death Race 2000. In the last year or two, programmers have been designing games that are less violent and more creative. Pac-Man and Frogger are good examples. So are the new interactive fiction games."

A Generation Of Loners?

Violence aside, some people argue that video games promote antisocial behavior. Maybe Galaxia won't make you want to shoot everything in sight, but how is a child or young adult going to learn how to interact with other people if he or she spends a great deal of time in an arcade or the house playing games on the home computer?

Christopher Cerf believes that computers foster, rather than hinder, communication. "Computers as a medium are one of the most exciting," he says. "They use elements of many other media.

"In schools, kids get excited about computing. They stay after school and compare notes and try to work out programming problems. And services like CompuServe and The Source also tend to bring people together. Kids who spend a lot of time alone with their computers or in arcades would probably be doing something else alone anyway.

"What's really interesting about this whole computer business is that, for the first time, the kids generally know more than the adults. My father was in publishing and he read everything—except science fiction. I loved science fiction and could recommend books to him. In that way, I think computers tend to bring families together."

Nothing For Women

There is little question that men are generally more interested in video games than women are at this point. Pac-Man was a breakthrough game in that sense; lots of women liked it, perhaps because of its apparent lack of violence.

Still, women are not leaping into the computer age with the same fervor as men seem to be. Mary Rowe, Assistant to the President at M.I.T., thinks that this is due to a lack of sensitivity on the part of many software producers. And to the fact that there is a lot of violence and sexism in video games.

"As a feminist, I'm concerned about the male slant of these things," Rowe says. "Why have computer companies made so few attempts to produce games that are not violent and sexist?

"Software companies need to be innovative about the uses of computers for women. And that means producing something that appeals to what women traditionally have valued and needed. Not violence."

Rowe does believe that some software companies are taking risks and developing programs that meet these needs. "I became computer-literate on Infocom's games. We need more games like that that require the player to actually think, not just hit the fire button at the right time."

Subtle Software

Nonviolent games fare very well on lists of best-selling software these days. Brøderbund's successful Choplifter is a good example. It's not an absolutely nonviolent game—there are terrorists and enemy tanks and guns going off. But the player does not get points for destroying things, only for rescuing people from the terrorists.

However, software companies which are producing nonviolent games are not necessarily trying to counteract any backlash against video games. Pat Marriot, of Electronic Arts, believes that people's opposition to video games is"an emotional thing. Parents wondering if their kids should be hanging out in arcades. Donkey Kong and Pac-Man are not really violent. It's just the environment of a video arcade that is disturbing.

"We look for quality and uniqueness in our programs," says Marriot. "We're not reacting against anything, we're going for quality. We look for authors whose values are consistent with those of the company. Each of our designers has a story to tell, and that story becomes the product.

"We don't really consciously try to make our games nonviolent, but because of our authors' basic philosophies, they usually do not involve violence," says Marriot. She points to Hardhat Mack as an example: "The character is very appealing. There's lots of humor in it. It seems to appeal to younger girls and to people who don't necessarily like games."

The Adventure Alternative

A video game doesn't have to have blasting guns and anguished screams to be violent. Even the pacifist Pac-Man has his own sublimated violence. He's a cute, nonthreatening little guy, but there are four potential killers on his trail. To avoid being destroyed, he must turn around and try to destroy them first.

It may be impossible to create a video game that does not incorporate some amount of violence, however unobtrusive it may be. Games involve competition. Even if you're just playing against yourself, you're always trying to overcome someone or something.

But in some games, you can actually benefit by resisting the urge to commit a violent act. In the text adventure Witness, by Infocom, you play a detective trying to solve a murder case. While you're trying to find the murderer, you have ample opportunity to rough up some of the suspects if you like. The game was designed to anticipate a variety of responses, even violent ones.

A violent response, though, is counterproductive, says Marc Blank, Vice-President of Product Development at Infocom. If a player reacts that way, the result is not good, and may lead to someone else getting killed.

Yet the designers at Infocom did not set out to produce games with pacifistic messages. "I don't think violence plays any part in our choices," says Blank. "We're not making a conscious effort to be nonviolent. We're just trying to produce programs of more literary quality."

This may be a contributing factor to Infocom's popularity with women, a market that software producers are sometimes finding difficult to please. "There is very little software for young women," says Blank. "Women generally read more than men, so our adventures are more appealing to them."

Better Technology?

Maybe the arcade is the monster, not the video game. According to an article in Newsweek (August 8,1983), video games peaked with an average weekly earning of $140 per machine in 1981, but last year it was down to $109. Is this because people are playing games at home on their personal computers and don't need arcades anymore? Or is it a result of the backlash against video games?

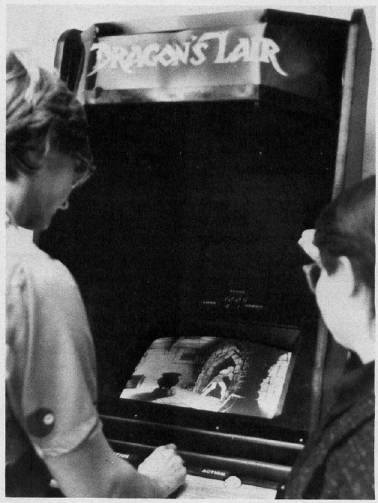

It may be neither. Dragon's Lair, an arcade game recently released by Bluth Animation, has people lined up around the block in some cities, waiting for their turn to play. Newsweek says single machines featuring this game are taking in up to $1400 per week. Even at 50 cents a crack, that's about a 500% increase over the current average earnings of arcade games.

Dragon's Lair is anything but nonviolent. Its hero, Dirk the Daring, must battle countless foes in 38 different scenes in order to rescue the game's heroine, Daphne.

But what's attracting people to it is a new technology that combines the use of laser disks and computers. Unlike other arcade games, this one projects a movie-quality image. It's like stepping into a cartoon and controlling the characters yourself.